Environmental Disaster at Salton Sea Is Now a Looming Public Health Crisis

Located in the middle of a desert, California’s Salton Sea — filled with abandoned buildings and beaches made of fish bones — looks like something out of Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), but the apocalyptic landscape didn’t always look this way. In fact, the area was once more popular than Yosemite National Park.

So, how did a bustling resort town turn into a desert wasteland? Here’s what’s going on with the Salton Sea, California’s strangest environmental disaster that could be the state’s next big public health crisis.

Where Is the Salton Sea?

Roughly 150 miles east of Los Angeles lies California’s swathe of the immense Sonoran Desert. Hedgehog, prickly pear and saguaro cacti fleck the otherwise empty landscape — until you reach a particular valley, just an hour south of Palm Springs.

In this particular valley, you won’t find saltbush or shrubs, let alone cacti. Instead, you’ll see nothing but an expanse of water. No, it’s not an oasis or a mirage. It’s the Salton Sea, California’s largest lake — and the state’s biggest mistake that just keeps growing.

What Is the Salton Sea?

Located right in the middle of the part of the Sonoran known as the Colorado Desert, the Salton Sea is a manmade lake. The lake’s surface covers about 343 square miles, and — ironically — it’s located 236 feet below sea level.

It occupies an expanse of valley that lies directly on the San Andreas Fault. Known as the Salton Sink, the area periodically filled with water and drained, thanks to the natural cycles of the Colorado River. However, everything changed in 1905.

Creation of California’s Largest Lake

Engineers from the California Development Company were attempting to bring water into the Imperial Valley to support the agriculture and farming in the region. To do so, engineers dug an irrigation canal from the Colorado River to the Alamo River channel.

Unfortunately, silt built up in the canals, forcing engineers to make a series of cuts in the bank of the Colorado to help maximize water flow. As you might guess, this created an overwhelming outflow of water, which flooded the Salton Basin, a once-dry lake bed.

Sustaining the Sea

The Salton Sea is now fed by the Alamo, New and Whitewater rivers — not to mention all the agricultural runoff. However, as an endorheic basin, the sea doesn’t drain very well. Instead, it acts as a basin, retaining water with no outflow to rivers or oceans.

Enough water feeds into the human-made lake each year to maintain its depth of 43 feet, but that has started to change dramatically within the last few years. The Quantification Settlement Agreement of 2003 put new restrictions on water inflow, resulting in a decrease in the surface area of the sea by about 60% between 2013 and 2021.

Farms Plant Roots in the Desert

Why the agriculture? Well, the entrepreneurial-minded folks in the early 1900s realized that if you could bring water to the Salton Sink area, you could feasibly grow crops year-round under the desert sun.

The Salton Sink went through a rebrand, marketed to buyers as the Imperial Valley. Folks looking to get into agriculture — or immigrate to the U.S. — bought up the land and bought into the endeavor. Unfortunately, the flood in 1905 destroyed homes and farms.

Stopping the Flood

Although the government of California knew about the flooding of Imperial Valley, officials did little to stop the disaster. The waters destroyed train tracks and homes and showed no sign of dwindling. The job of cutting off the water flow fell to Southern Pacific Railway.

The company built train tracks out to the cut in the canal, and workers toted all sorts of old junk — from car parts to hunks of cement — to the breach, hoping to build a solid foundation on the river’s sandy bottom. This went on for an entire year before workers were finally able to reroute the river back into the channel.

The Sea Becomes Permanent

In many ways, Southern Pacific Railway’s efforts were too late. Sure, they staved off the destruction of more farmland and homes, but the Salton Sink had completely flooded. Locals believed the man-made accident would dry up.

After all, it had been filling with water and drying up for millions of years when the Colorado River flowed in periodically. Sadly, this was not the case. Water did evaporate from the lake in the desert sun, but it was also quickly replaced by runoff from the new irrigation systems. The Salton Sea was here to stay.

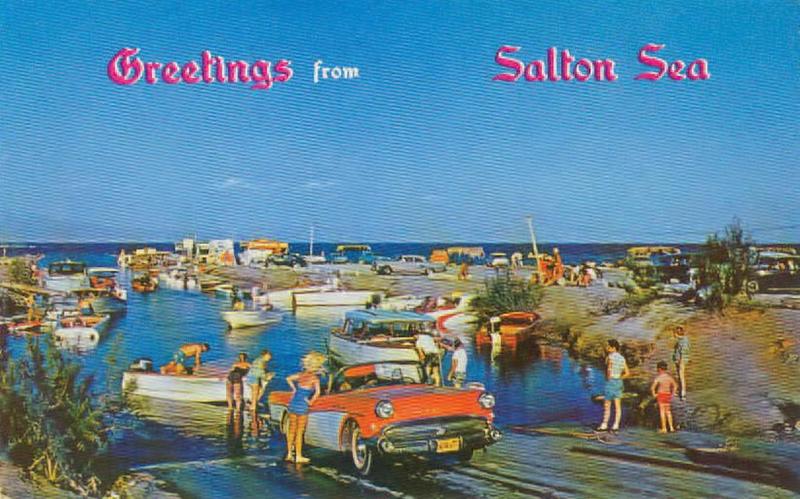

The Tourist Boom Begins

While this was technically the first natural disaster to strike the Salton Sink, it sure didn’t look like a disaster — at least not to folks who didn’t lose anything during the flood. In fact, to real estate developers and clever salespeople, the Salton Sea presented a new opportunity.

A vast body of water, clear and pristine — and right in the middle of a desert. In many ways, it was a picturesque oasis. Soon enough, it was marketed to wealthy Los Angelinos as a beach-like playground located just a stone’s throw from Hollywood.

Something Fishy Arrives

The only thing the Salton Sea was missing? Fish. The California Department of Fish and Game became eager to stock the sea so visitors could flock to the lake for some sportfishing. Researchers at UCLA (and elsewhere) designed an entire ecosystem for the sea, introducing a variety of fish from both saltwater and freshwater environments.

Besides the short-lived introduction of harbor seals, perhaps the most unique species introduced was the Mozambique tilapia. (But more on that later.) Soon enough, the Salton Sea became one of the most popular fishing destinations in the country, with its marinas welcoming more visitors than Yosemite National Park.

1950s: Resort Boom in the California Riviera

Called the “California Riviera,” this waterfront Palm Springs became a popular resort area during the 1950s, complete with water skiing and speedboats. One early adopter was oil tycoonPenn Philips, who established Salton City on the sea’s western shore. Philips built a yacht club, cut the land into lots and brought in busloads of buyers.

Soon, parcels of land were being snatched up fast. At the height of the resort area’s popularity, prospective buyers from Los Angeles were allegedly flown over the land in helicopters. From the sky, they could pick out the spots they wanted.

1960s: Stars Power the Sea

The first tourists to discover the California Riviera were Hollywood’s elite. Star-studded clubs, including Ace & Spades and the 500 Club, became hotspots for partying and boating. An annual crowd of 500,000 non-Hollywood visitors soon descended upon the Salton Sea, eager to mingle with celebrities.

Sonny Bono — later mayor of nearby Palm Springs — learned how to water ski on the sea, surrounded by other greats like Frank Sinatra and Jerry Lewis. Later, when the area faced environmental hardships, he became one of the Salton Sea’s greatest champions. Famously, the Beach Boys were members of the North Shore Beach Yacht Club.

1970s: The Price of Salt

Unfortunately, after the heyday of the ’50s and ’60s, the party died down. Following a devastating, infrastructure-destroying flood in the 1970s, many business owners decided against rebuilding. Why? The water’s salinity was becoming a massive problem.

Because the sea doesn’t flow into any other bodies of water, the salts in the water have nowhere to go and are simply left behind during the evaporation process. These days, the sea’s salinity is nearly twice that of the Pacific Ocean, increasing at a rate of roughly 3% each year. According to a study conducted by the University of California, an estimated 4 million short tons of salt are deposited into the valley annually.

1980s: The Decline Worsens

As the sea grew saltier and saltier, the tourists became fewer and fewer. All that salt was hard on fish populations, and species began dying off en masse. Once sandy beaches turned to white bone beaches, and no one wants a beach house that’s fish graveyard-adjacent.

Massive algae blooms — mats of scum containing cyanobacteria — sprouted on the water’s serene surface. The bacteria fed on the fertilizer and waste runoff from nearby farms, growing at a rapid rate in the desert sun and sometimes spewing harmful toxins. If all that wasn’t enough to drive people away, the smell — think rotten eggs baking in the hot sun — certainly sealed the deal.

1990s: The Sea Dries Up

Although most Californians wanted nothing to do with the slowly-dying sea, some folks stuck it out. Finally, in 1986, the state announced that no one should consume fish caught in the Salton Sea, as the toxicity levels were deemed hazardous.

As farms became more water-efficient in the ’90s, there was less runoff flowing into the sea. Less runoff meant the water that evaporated was no longer being replaced at the same rate, leading to large swathes of the Salton Sea drying up.

A Water Transfer Causes Waves

In 2003, the folks in charge of Imperial Valley — which shares the Salton Sea with the neighboring Coachella Valley — sold off the land’s water rights. The city of San Diego, located just a few hours southwest of the sea, was the buyer.

The 99% Invisible podcast reported in a 2016 episode that back in 2003, when the water transfer took place, the deal was made without a proper review of the environmental impact the transfer would have on the sea. Irrigation was handled with more care — meaning the sea had even less water trickling in than before.

Mozambique Tilapia Crowd the Beaches

Okay, so what’s living there now? Considered to be one of the world’s most invasive species, the Mozambique tilapia is putting up a good fight against the water’s salinity, but there’s little the population can do to combat other issues, namely, the lack of oxygen in the water, which is eaten away by runoff and toxins.

Bacteria turn the dead fish into corpse wax, and bones wash up on shore. According to the Los Angeles Times, roughly 7.6 million fish died per day in the ’90s. For reference, that’s about the entire population of the San Francisco Bay Area.

A Migratory Bird Sanctuary

Dubbed the “crown jewel of avian biodiversity” by the Salton Sea Science Office’s Dr. Milt Friend, the former California Riviera has the second-most diverse avian population in the U.S., falling just behind Texas’ Big Bend National Park.

More than 400 species of birds have been known to visit the former resort area, especially migratory birds, due to the destruction of most of California’s wetlands.Despite being a sanctuary of sorts, the area has experienced several documented massive bird die-offs. The deaths are most likely linked to the winged animals’ consumption of toxic fish, the spread of disease and the sea’s receding waters.

Resort Towns Revisited: Salton City

Oil magnate and land developer Penn Phillips established Salton City hoping to serve 40,000 residents. Starting in the ’70s with the onslaught of floods along the shore and continuing into the ’80s with the growing concerns over toxicity and salinity, the Imperial Valley’s largest settlement became a shell of the resort town it was planned to be.

Today, the U.S. Census Bureau reports that 81% of the lots in Salton City are undeveloped. Nearly 40% of residences — at least the ones deemed habitable — remain empty. Although a reported 3,763 people call Salton City home, its abandoned buildings give it the look of a ghost town.

Resort Towns Revisited: Bombay Beach

Across the sea from the once-popular Desert Shores and Salton City lies Bombay Beach, a former tourist hotspot on the eastern shore. According to the 2010 census, just 295 people call the town home. The median household income was reported to be around $17,708.

With the nearest gas station 20 miles away in the town of Niland, most folks travel between the town’s lone bar, Ski Inn, via golf cart. Although a berm — a raised strip of land bordering a canal — shields what is left of the town, a portion of Bombay Beach is buried in mud. Due to its post-apocalyptic look, the town is a popular subject for photographers.

The Most Polluted River in the United States

Although the river channel has existed for centuries, what is now called New River (or Río Nuevo) was formed during the same incident that “created” the Salton Sea. The river flows north toward the Salton Sea, through Mexicali, Baja, Mexico and into Calexico, California.

Since the early ’90s, the California Regional Water Quality Control Board has deemed it the most polluted river of its size in the U.S. And that’s probably because most of its water is a cocktail of agricultural runoff, sewer discharge and industrial wastewater. Best to avoid fish caught in the New River — unless you like your dinner with a side of mercury and selenium.

The San Andreas Fault

To make matters worse, the Salton Sea is located on the southernmost portion of California’s infamous San Andreas Fault. According to the Los Angeles Times, seismologists have long feared the sea “could be the epicenter of a massive earthquake.”

As reported by San Francisco-based KRON4 in 2018, the 15-mile long, recently-identified “Durmid Ladder” structure (pictured here) could trigger something devastating. “If you… break a rung… then the ladder beings to deform,” explains Dr. Walter Mooney of the U.S. Geological Survey. “If you break another rung… both sides could go.”

A “Slow-Moving Natural Disaster”

Called a “slow-moving natural disaster” by the Los Angeles Times, the latest threat identified in the Salton Sea area is a bubbling, muddy spring. And it seems to be on the move, cutting its way through dry earth.

Like a sinkhole, this muddy spring gets around. According to Imperial County officials, the spring moved 60 feet in a few months — but its clip increased to 60 feet in a day. The muddy spring threatens nearby railroad tracks, a pipeline, a stretch of Verizon’s telecommunications lines and part of Highway 111, near the town of Niland.

Geothermal Vents & Mud Pots

Although they look like hot springs, so-called mud pots near the Salton Sea don’t spout mud because they’re boiling. Instead, the mud pots are a natural way for carbon dioxide formed beneath the Earth’s surface to escape.

As the Salton Sea has dried up, these once-underwater mud pots have been exposed. Now, the Imperial Valley Geothermal Project has installed 10 generating plants to harness the area’s geothermal energy. Although this renewable energy source seems like a great way to revitalize the area and harness its natural resources, CalEnergy backed out of a plan to utilize the geothermal reservoir.

Toxic Dust Storms

If a muddy spring devouring the desert and disastrous earthquakes aren’t terrifying enough, the Salton Sea is also a breeding ground for toxic dust. With the lakebed drying up, toxic dust particles are more likely to be swept up into the air.

These dust storms, containing heavy metals and other harmful deposits from runoff and wastewater, could cause respiratory issues like asthma for folks in the affected areas. Toxic dust particles could be carried as far as Los Angeles, San Diego and Phoenix, Arizona, a whopping 300 miles away.

Discounting the Sea: Environmentalists

With all these issues, why isn’t more being done to save the Salton Sea? Well, a lot of environmentalists actually discount the importance of the sea — or at least they discounted its legitimacy in the past — and now that initial negligence has added up.

To some, the sea is purely man-made — an accident. But this argument discredits the fact that the Salton Sink has a rich geological history. For years, the Colorado River periodically flooded the land, which then naturally dried up. After the “accident,” wildlife adapted, creating a new ecosystem.

Discounting the Sea: Lawmakers

If environmentalists discount the significance of salvaging the Salton Sea, you can bet that lawmakers have also largely discounted it and ignored its problems. After all, the sea falls into that “out of sight, out of mind” category — until the tell-tale stench wafts into LA.

As reported by the 99% Invisible podcast, the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California concluded that the cost of ignoring the Salton Sea’s problems could total $70 billion over the next 30 years. With the impending toxic dust threat becoming more likely as the sea dries up, the state sent water to the area for a while to help keep the salinity down. However, that inflow of water stopped in 2017.

Bombay Beach Re-Imagined

Remember Bombay Beach? In recent years, the nearly abandoned town has seen a sort of artistic rebirth. Artists and hipsters looking to find bohemian spaces out in the desert have started to transform the derelict buildings into crafted installation art pieces.

If you visit Bombay Beach today, you will find an opera house, gallery spaces, a drive-in movie theater and even a “Hermitage Museum.” Many of these works of art were established as part of the Bombay Beach Biennale, a “renegade celebration of art, music and philosophy that takes place each year on the literal edge of western civilization.”

Beachfront Property That’s Fish Graveyard Adjacent

Thanks in part to the Bombay Beach Biennale, a new wave of artists and hipsters have descended upon the town’s desolate shores. According to The Guardian “some bungalows which cost a few thousand dollars 15 years ago now fetch tens of thousands of dollars.”

According to a writer at Roadtrippers, the locals don’t seem worried that the artists’ revitalization will gentrify Bombay Beach. Seemingly, they feel optimistic that their community will experience the benefits of the spotlight without the drawbacks that claim so many city neighborhoods.

Desert Oddities: Salvation Mountain

Even apart from Bombay Beach, “outsider artists” thrive in the desert. Northeast of Niland and just outside a place called Slab City stands a visionary environment known as Salvation Mountain, a large-scale art installation 50 feet high and 150 feet wide.

Built by local artist Leonard Knight (1931–2014), Salvation Mountain is a “tribute to God,” made of adobe clay, straw and buckets of colorful paint. The sculpture has been called “a folk art site worthy of preservation and protection” by the Folk Art Society of America. Around it, other installations have cropped up, reiterating Knight’s desire to revitalize the Salton Sea area.

Desert Oddities: International Banana Museum

Perhaps it’s no surprise such a strange desert is full of other oddities-turned-tourist-destinations. For example, in the nearby town of Mecca, which lies between the Salton Sea and Palm Springs, stands the International Banana Museum. (Appeeling, right?)

The small “museum” contains a collection of more than 25,000 banana-related items and pictures. Visitors can take a photo with a human-sized banana sculpture, try on funny clothing, taste homemade banana shakes and — as the proprietor suggests — go bananas!

The Future of the Sea: Financing Change

Despite these ad hoc initiatives by artists to draw tourists to the area, the Salton Sea’s future remains uncertain. Between 2000 and 2008, millions of dollars in initiatives at the state and federal levels never materialized. However, in January 2016, California approved an $80 million allocation for the sea.

Furthermore, the U.S. Department of the Interior and the California Natural Resources Agency signed a memorandum that secured a federal commitment of $30 million for “dust suppression and habitat restoration projects.” The state also released a 10-year plan in 2017 that focused on mitigating damage instead of restoration. Of course, it might be too little too late.

The Future of the Sea: Uncharted Territory

Throughout 2018 and 2019, Palm Desert’s Rep. Raul Ruiz, M.D., has worked to secure additional funding, the creation of foundational legislation and — perhaps most importantly — commitments from federal agencies to alleviate the imminent health crisis and environmental issues.

A way forward is complicated, primarily because the Salton Sea’s predicament is otherwise unheard of, and there’s no roadmap to follow. After years of neglect, California’s largest lake may (accidentally) become the state’s largest disaster — again.