Yes, Jorō Spiders Parachuting Over the East Coast Is a Real Threat — Here’s Why

You read that correctly — spiders parachuting down over the East Coast of the United States might be a reality this year. While 2020 brought us swarms of murder hornets and 2021 ushered in the brood X cicada emergence, 2022 might just take the prize for strange animal-related news.

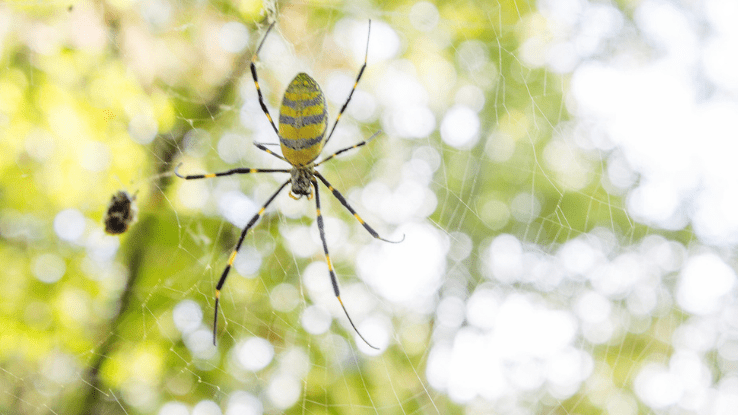

If you live in Georgia or South Carolina, you may have noticed a new neighbor in your garden — a bright yellow and red spider about the size of an adult human’s hand. Trichonephila clavata, better known as the Jorō Spider, recently traveled here from Asia. Found natively throughout China, Korea, Taiwan, and most of Japan, these spiders have also been thriving in Georgia and South Carolina recently — and their numbers in the States are only increasing.

If you live in one of the states along the East Coast, you may happen across one of these large arachnids in your garden in the near future. Experts believe that they may begin populating the area in more noticeable numbers as early as this year. The progression tracks with their rapidly expanding numbers over the last year, not to mention that the spiders’ physiology makes them particularly well-suited to the colder climate along the Eastern Seaboard.

What Is a Jorō Spider?

Jorō spiders are a type of orb spider from the family Araneidae. The Araneidae family of spiders is a huge family that’s best known for their wheel-shaped webs. A few orb spiders, like the bolas spider, spin atypical webs instead of the traditional circular or spiral webs. Jorō spiders produce webbing that appears gold in the sunlight, and they use this striking webbing to construct round, orb-like shapes. The web structures the Jorō spiders create are often large and three-dimensional — some even reached an astounding 10 feet deep.

Female Jorō spiders are large, reaching approximately three inches across, and sport bright yellow stripes across their jet-black bodies as well as striking red patches on their sides. On the other hand, male Jorō spiders, which are a more subdued brown, are around a third of the size of their female counterparts. Despite their differences, both male and female Jorō spiders are skittish and avoid contact with people and other spiders.

How Are These Parachuting Spiders Spreading?

To expand their territory, these adaptable arachnids have used two methods, for the most part. The first method? They hitch a ride. Spiders are excellent hitchhikers, after all, and they can easily pick stow away in a car, truck, train or cargo vessel. Some female Jorō spiders may even attach their egg sacks to moving vehicles, resulting in greater spider distribution. These colorful eight-legged invaders are believed to have originally hitched a ride from Asia — some experts believe Japan — in a shipping container to get to the southern United States.

What about the second method of travel? This brings us to the whole “spiders parachuting” ordeal. This species makes a sort of a parachute from their webbing and then use that web-parachute to ride the wind currents. Baby spiders, known as spiderlings, frequently use this method to disperse from their nest, and adult spiders can use their webs to glide up to 100 feet on air currents.

Scientists compared Jorō Spiders to another orb spider that immigrated into the Georgia area, but hasn’t expanded its range so much — the golden silk spider. Research has shown that Jorō spiders had a 77% higher heart rate than their golden silk spider cousins when exposed to low temperatures, which means the Jorō spider is more able to survive a drop in temperature.

Jorō Spiders Parachuting Down Isn’t Something to Fear — Necessarily

In Asia, the bright yellow arachnids share their name with one of the most well-known of the arachnid yōkai, a type of supernatural entity from Japan. The Jorōgumo yōkai are said to be cunning shapeshifters who can change from the form of a spider to that of a beautiful woman. This ability helps them lure in men so that they can devour these unsuspecting suitors.

But despite their large size and fearsome reputations, Jorō spiders are extremely timid arachnids. In fact, they’re more timid than most of the spider species endemic to North America, making them something of a gentle giant — and not really movie monsters.

In addition to their timid nature, most Jorō spiders have mouthparts that are too small to penetrate skin. Even if they could penetrate your skin, their venom is relatively harmless to humans. On rare occasions, a bite from a Jorō spider can cause redness and swelling, comparable to a bee sting, which can last for up to a day or two. Although they aren’t a physical threat to people, their expansive webs sometimes interfere with gardening.

How Jorō Spiders Parachuting Down on the East Coast Will Impact the Environment

Some invasive species, from emerald ash borers (EAB) to Burmese pythons and feral hogs, can completely upset an ecosystem. Others may not have as much of an effect. Jorō spiders don’t seem to be displacing any of the local species at this point. Their preferred diet is composed of lanternflies, mosquitos, and stink bugs. Some of these insects, like Asia’s brown marmorated stink bug, are considered pests in North America, which actually makes these parachuting spiders somewhat helpful.

While these spiders aren’t dangerous to humans or pets, you might be concerned about the potential of the Jorō to push out local arachnids. Not to mention, their exceptionally large webs may negatively impact pollinators, such as already-distressed bees, as well.

Early signs indicate that Jorō spiders may have a positive effect on the ecosystem over time; for now, we’re just happy to hear that there doesn’t seem to be a measurable negative impact.