Et tu, Brute?: The Downfall of Julius Caesar

You might already know the tragic tale of Caesar, the famed Roman leader who was murdered by his friends and foes in the Senate — but do you know the story behind his downfall? Caesar’s legacy is complicated, but his story has inspired novels, plays, films, television shows and other cultural retellings worldwide. Still, the actual narrative of Caesar’s death — particularly the motivations and the aftermath — is often shaded beneath the circumstances of the murder. To mark the Ides of March, the date of Caesar’s assassination, we’re taking a look into what led the Roman elite to kill Caesar and how the aftermath resulted in the fall of the Roman Republic.

How Caesar Reshaped Rome (for Better and Worse)

Caesar is one of the most significant figures in Roman history, and for good reason. Throughout his life, he involved himself in the affairs of his people and state. Through charisma, wit and brute strength, Caesar made his way to the top of the ranks in the Roman military, gaining fame for his conquest of the Gallic people and his epic rivalry with the fallen Roman leader Pompey.

Following his military service, Caesar progressed quickly through the political chain. It didn’t take long for his wartime reputation to lend itself to an even more favorable political career. Between 69 B.C. and 59 B.C., he transitioned from a low-level quaestor, a type of public officer, to a consul, the highest-level official in Roman politics. At the peak of his life — and not long before his death — he was the most powerful man in the Roman Republic.

On the surface, Caesar didn’t seem to burn any bridges with the Roman public. As a politician, he spearheaded efforts to expand Rome, including ordering the reconstruction of Carthage and Corinth, two notable ancient cities destroyed in previous wars. He also worked to improve the lives of working class Romans, providing supplies, land, and debt and rent forgiveness and working to remedy the financial gap between the classes. For these efforts, Caesar was beloved among Rome’s working-class citizens.

However, Caesar’s image suffered from a lack of clarity around his intentions. Did he actually care about Rome, or only his own ascension? To his fellow elites, it seemed that he had begun to steer Rome beyond a republic and into a system of imperialism. In the end, he seemed intent on taking his place at the top of the government. And this didn’t sit well with the Roman Senate.

Why Was Caesar Murdered?

The motivations for Caesar’s murder aren’t entirely straightforward. Caesar’s infamous role in Roman expansion meant that he had a complicated relationship with the people of his government, some of whom looked upon him with adoration and others who felt angered by his perceived grabs for power. However, he was likely killed for one primary reason: fear of dictatorship. Caesar’s upward ascent to power didn’t seem to have an endpoint. Politicians around him began to grow nervous that he might usurp their power and take over all of Rome. The former rulers of Rome, the Etruscan kings, had been power-hungry tyrants. Memories of their rule led to the distrust around Caesar’s empowerment.

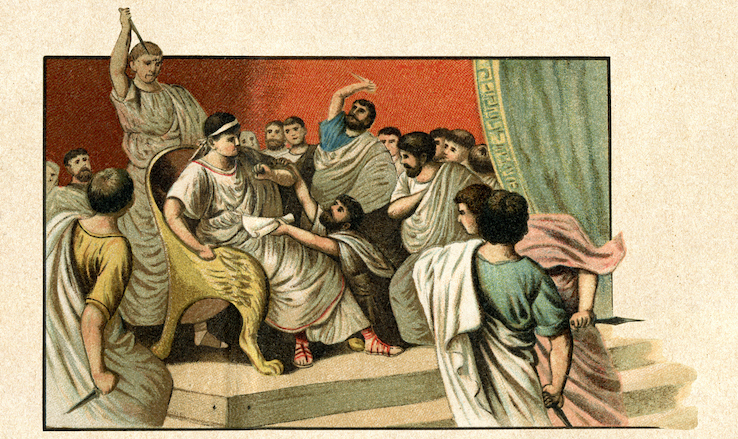

In 44 B.C., two Roman politicians named Cassius Longinus and Marcus Brutus (one of Caesar’s closest friends) discussed ways to prevent Caesar from seizing power over the country. Worried that Caesar would push them into a tyrannical government, the two began to expand their circle of concern to include other politicians, Senators and nobles. Soon, many of Caesar’s colleagues were in on the plot to end Caesar’s impending reign. But how? Cassius and his conspirators saw the murder of Caesar as the only clear way to liberate themselves and the country from his imperialist ambitions.

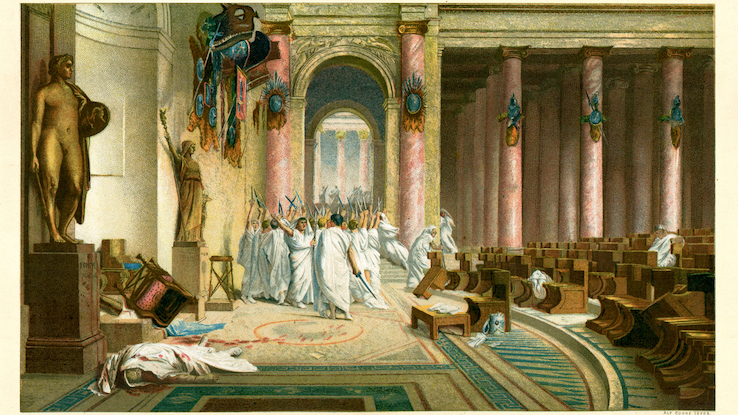

How Did the Murder of Caesar Unfold?

Unfortunately for Caesar, he was an easy target for assassination. He yearned to lead a semi-normal life and did not use bodyguards. The Senators intended to kill him on the Ides of March — March 15 in 44 B.C. — by drawing Caesar to the location of the Gladiator Games, the Theatre of Pompey, and stabbing him.

When Caesar didn’t show up to the fake event, they sent Brutus to retrieve him. Brutus had become Caesar’s long-time confidant after Caesar pardoned him following a battle. He had become like Caesar’s own child, which meant that he had little trouble persuading Caesar to follow him. Caesar brought Mark Antony, a close ally, along. The assassinators lured Antony away and left Caesar with no cover. Once he was alone, someone grabbed Caesar’s toga, fellow Senators drew their blades and the attack began.

The assault lasted only minutes, but Caesar ended up with nearly 30 wounds. He bled out and passed away on the theater floor. Historians speculate that his heartbreaking final words were “Et tu, Brute?” — meaning “You too, Brutus?” — conveying the shock Caesar felt that, even after pardoning Brutus, the man would participate in Caesar’s violent assassination. However, Brutus, along with the rest of the Senators, felt justified in the attack, believing it would prevent the Roman government from falling victim to tyranny. But how did the rest of Rome feel when they found out about the assassination?

What Was the Immediate Aftermath?

Caesar’s death was not a finalizing event. After Caesar was killed, the Senators sent Brutus to speak to the citizens and explain their intentions behind the murder. Brutus met with the Roman public and conveyed that, had they not killed Caesar, he may have taken over as King of Rome and threatened their liberties and rights.

While this seemed perfectly reasonable to the Roman elite, the common people of Rome were not satisfied with the reasoning. His murder echoed throughout the state, and the middle- and lower-class people of Rome were furious that the Senate had taken their leader’s life. The assassination also led to a series of civil wars. The lower classes rose up against the elite, with Mark Antony and his allies rallying against Cassius and Brutus’ armies in Greece.

Meanwhile, Caesar’s heir, an adopted grand-nephew named Octavian, found out about the death of Caesar while training at a military camp. He came to Rome to inherit Caesar’s fortune and found himself swept into the unfolding battles for power and wealth that resulted in additional years of conflict. The wars between Cassius, Brutus, Antony and Octavian led to an ongoing loss of life and contributed to public unrest throughout an increasingly less manageable state.

Ultimately, it took another 17 years before the Roman Republic ended and the Roman Empire developed. Octavian, renaming himself “Caesar Augustus,” took his place as the first Roman Emperor, spurring a new political horizon for Rome.