Civil Rights Leaders You Won’t Read About in History Books

While Malcolm X, Rosa Parks and of course Martin Luther King Jr. are all well-known leaders in America’s civil rights movement, the accomplishments of that era were the work of more than just a few individuals. Thousands marched, organized, educated and more to build a better society, and as a result, some leaders fell by the wayside of many of today’s history books. These are just some of the amazing civil rights leaders you may have never learned about.

Claudette Colvin

Although Rosa Parks may be famous for refusing to give up her seat for a white man, Claudette Colvin stood her ground nine months earlier — and at the age of 15 rather than 42. She and three of her friends were sitting in a row when a white woman boarded the bus, and the driver demanded that all four of them move. Three did. Claudette didn’t.

She explained that it was her constitutional right to sit there. “It felt,” Colvin later explained, “as though Harriet Tubman’s hands were pushing me down on one shoulder and Sojourner Truth’s hands were pushing me down on the other shoulder.”

Colvin’s books were knocked from her hands, and she was manhandled off the bus and later placed in jail before being bailed out by her parents. The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) considered promoting her as a key figure in the fight against segregation, but it ultimately chose not to because she was a teenager. She also soon became pregnant, which organizers feared would distract from the broader struggle.

Even so, along with Aurelia S. Browder, Susie McDonald and Mary Louise Smith, Colvin became one of four plaintiffs in the case of Browder vs. Gayle, which saw Montgomery, Alabama’s bus policies thrown out as unconstitutional. Colvin moved to New York City two years later and became a nurse’s aide.

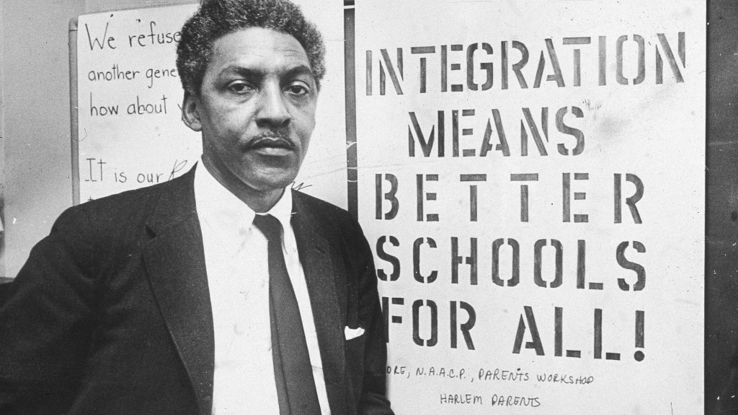

Bayard Rustin

While Martin Luther King Jr. was the face of the civil rights rallies of the ’60s, Bayard Rustin was the man behind the scenes who organized them. Raised by his teenage mother and Quaker grandparents, he was drawn to the Young Communists League while attending New York’s City College during the 1930 because of their support for racial equality. However, he left when the Communist Party shifted away from civil rights work after 1941. He then joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), co-founded the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and became an active campaigner for civil rights.

Rustin’s accomplishments are almost too numerous to list. He participated in CORE’s Journey of Reconciliation, the predecessor to the later Freedom Rides that ended bussing segregation, and ended up on a chain gang as a result. He used that experience to publish several newspaper articles that led to the reform of such gangs. In 1948, he went to India to see Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent practices in action, and he later traveled to West Africa to work with different colonial independence movements. He became a close advisor to Martin Luther King and played an instrumental role in everything from 1963’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to helping to draft King’s Memoir, Stride Toward Freedom.

Rustin became a target of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI early on because of his communist ties, and his 1953 conviction on charges of homosexual activity caused tension even with other civil rights leaders. Nonetheless, Rustin continued his work, and in the 1980s, he finally opened up about his sexuality. He played a key role in getting the NAACP to take action against the AIDS crisis. He died in 1987.

Shirley Chisholm

Born to immigrant parents from British Guiana and Barbados, Shirley Chisholm graduated from Brooklyn College in 1946. She was an education consultant for New York City’s daycare system and was active in the NAACP before representing Brooklyn in the New York’s state legislature from 1964 to 1968. She then achieved success on the national stage by winning election to the House of Representatives, where she remained until 1981. She was an ardent opponent of the Vietnam War and a supporter of abortion rights and the Equal Rights Amendment.

Chisholm was also both the first Black person and first woman to run for the nomination of a major party in the United States. Though she only received 152 delegate votes at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, her run nevertheless foreshadowed even greater political accomplishments for women and people of color in the years and decades to come.

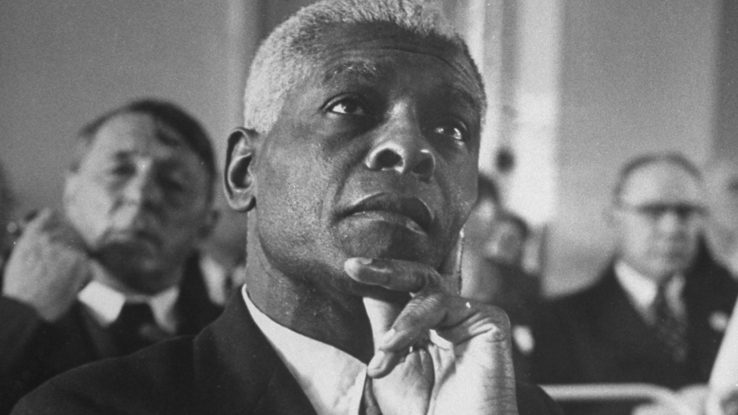

Benjamin Mays

Martin Luther King Jr. once described Benjamin Mays as his “spiritual mentor.” Born in 1894 Hezekiah and Louvenia Carter, who were former slaves, Mays grew up to get a doctorate from the University of Chicago and was ordained as a Baptist minister. He later became president of Morehouse College.

While at Morehouse, Mays delivered weekly addresses at the college’s chapel, and it was these speeches that first drew a young Martin Luther King Jr. to him. King began meeting with Mays to discuss theology and world affairs after the weekly addresses, and Mays began to have Sunday dinners with the King family.

Mays went on to be one of King’s most prominent supporters. When mass arrests led King’s father to ask him to step down as a leader in the Montgomery bus boycott, Mays vocally supported King’s decision not to do so. He gave the benediction at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Even after King’s assassination, Mays continued to fight for civil rights and became the first Black president of the Atlanta Board of Education.

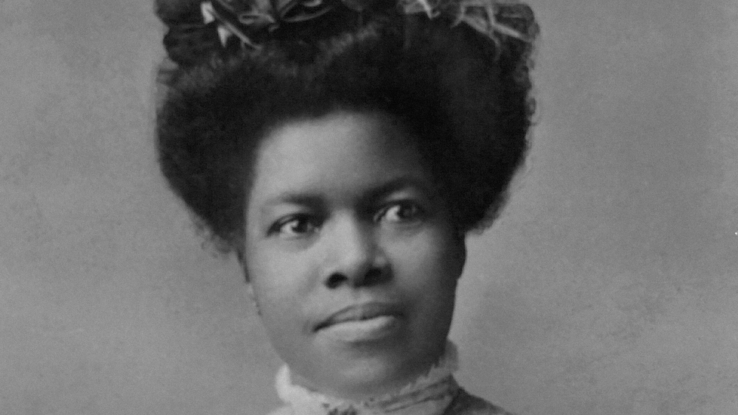

Nannie Helen Burroughs

Like Mays, Nannie Helen Burroughs’ parents had experienced the horrors of slavery firsthand. After her father died, she and her mother moved to Washington D.C. Burroughs performed well in school, but despite her success, she was unable to find a job as a public school teacher. As a result, she decided to found her own school for Black American women without the means to pay for an education.

Some civil rights leaders of the time, such as Booker T. Washington, doubted Burroughs’ ability to raise money for the school. Because of donations from local black women and their families, however, Burroughs was nevertheless successful, and the National Trade and Professional School for Women and Girls (NTPSG) in 1909 with the motto, “We specialize in the wholly impossible.” At age 26, Burroughs was the first president.

The NTPSG was unusual in that it combined a classical education along with vocational skills meant to help black women find jobs in modern society. Black history was also a required course, a largely unprecedented move for the time. While the original school only consisted of a small farmhouse, in 1928, it grew to include a larger building with 12 classrooms and additional facilities. Burroughs died in 1961, but her efforts to provide education and opportunity regardless of race or gender paved the way for further efforts to secure civil rights.