Why Should We “Remember The Alamo”?

The Battle of the Alamo was fought between February 23, 1836, and March 6, 1836, as part of Texas’ war for independence from Mexico. The battle would long after be referenced with cries of “Remember the Alamo!”

But what is the Alamo? Who died at the Alamo, and why is it such a famous part of American history? Join us for a trek back in time as we explain what exactly went down at the Alamo through the lens of history.

The Alamo’s Early History

The Alamo was originally a Spanish mission near the present-day town of San Antonio, Texas. While we all know that Texas has long been part of the United States, it’s important to keep in mind that this wasn’t always the case.

When the Alamo was first built in 1718, it was called the Mission San Antonio de Valero, and Texas was still a territory of Spain. Originally it housed Spanish missionaries and the Native American “converts” they had forced to join their ranks.

By the time Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, however, the mission had been abandoned. It eventually became a sort of makeshift fortress where soldiers from the Alamo company, named for their hometown of Alamo de Parras, were stationed. The soldiers eventually dubbed the fortress “El Alamo,” which means “The Cottonwood” in Spanish.

Though Texas was now firmly in Mexico’s custody, it began attracting plenty of American immigrants, many of whom secured land grants with the help of figures such as Stephen Austin. The immigrants were able to settle in Texas with the blessing of the Mexican government, at least for a time.

The Seeds of Texas Independence

In 1833, Mexico elected a new president, a powerful military general named Antonio López de Santa Anna. While many Mexican nationals and American immigrants alike felt that the government should have more power at the local level, the new President disagreed. He began to move towards a more centralist government model in which the national government would have almost complete power over state and local governments.

But this was far from the only issue. While often swept under the rug, slavery played a major role in the sparks that ignited the Texas Revolution. Many early Texans had immigrated from the American South and became angry when Mexico attempted to outlaw slavery. This has become a controversial point among scholars to this day, due to the obvious moral issues it poses regarding whether the Battle at the Alamo should be celebrated.

Ultimately, tensions reached a boiling point and Texas decided to seek independence from Mexico. On October 2, 1835, the first shots of the Texas Revolution, aka the War of Texas Independence were fired in what would become known as the Battle of Gonzales.

The Texans Seize the Alamo

By December of 1835, Texas’ war for independence was well underway. A group of Texan military volunteers, led by George Collinsworth and Benjamin Milam scored a major victory when they were able to overpower a Mexican garrison that was stationed at the Alamo.

The victory had secured the Texan’s control over San Antonio, and by February of 1836, Colonel James Bowie and Lt. Colonel William Travis had arrived to take command. Also in attendance was Texan commander-in-chief Sam Houston. When it became obvious that the president planned to retaliate, Houston suggested that the stronghold be abandoned due to the low number of men stationed there.

But Bowie, Travis, and the Alamo’s other defenders refused to budge while Houston went for reinforcements. Unfortunately, most of them wouldn’t arrive in time, though a few more men joined in time for the battle. Among them was the famed frontiersman Davy Crockett. Regardless of the defenders’ enthusiasm, however, the number of troops stationed at the Alamo never grew beyond 200 men.

The Battle for the Alamo Begins

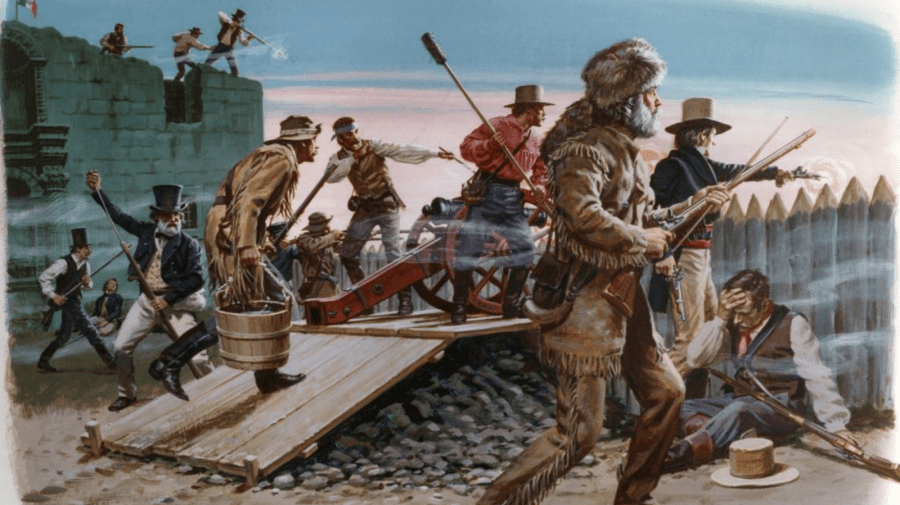

A powerful military general in his own right, President Santa Anna led a Mexican army to the Alamo himself, in order to squash the Texan rebellion once and for all. Though accounts vary, it’s estimated that he arrived on February 23 with anywhere from 1,000 to 1,600 men under his command.

For the next 13 days, the defenders of the Alamo refused to surrender, even though they were clearly outnumbered. Santa Anna had made it clear that his army would take no prisoners and that the battle would be fought to the death. After more than two weeks, the Mexican troops finally launched a major attack on the Alamo on March 6, 1836.

While the Alamo’s defenders were able to hold them off for a while, ultimately, the Mexican army managed to infiltrate the fort and kill nearly every soldier inside. As far as how many people died at the Alamo, we don’t have an exact figure. But we do know that when the fighting was finished, around 15 Texans were left alive, most of whom were women, children, or slaves.

So, did Davy Crockett die at the Alamo? He did indeed, along with James Bowie and William Travis.

“Remember the Alamo”

While the phrase is still commonly referenced today, the Battle at the Alamo was actually a terrible loss for Texas. One of the reasons it became so important was that it really riled up the rest of Texas and made them even more determined to win independence from Mexico.

The Texas war for independence finally met its end on April 21, 1836, when Sam Houston led an army of Texans to victory in the Battle of San Jacinto. Throughout the battle, which lasted only about 18 minutes, the Texans descended on their enemies as they cried “Remember the Alamo!” It was a way of announcing that even though the Texans might have lost the battle, they fully intended to get even by winning the war.

Today, a large monument stands on the historical San Jacinto battlefield. As one of its inscriptions describes the battle’s importance; “measured by its results, San Jacinto was one of the decisive battles of the world. The freedom Texas won from Mexico eventually led to annexation — and to the Mexican War, resulting in the acquisition by the United States of the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. Almost one-third of the present area of the American nation, nearly a million square miles of territory, changed sovereignty.”