Inspiring Women Civil Rights Icons Who Fought for Equality

Women activists, abolitionists and political leaders have made crucial contributions to the ongoing fight for civil rights in the United States. While the role of these women can sometimes be overlooked, their impact and influence cannot be understated. Below, we’ve highlighted five women civil rights pioneers whose powerful stories can help teach us about the importance of fighting for equal rights and the power of dedicated individuals to create positive change.

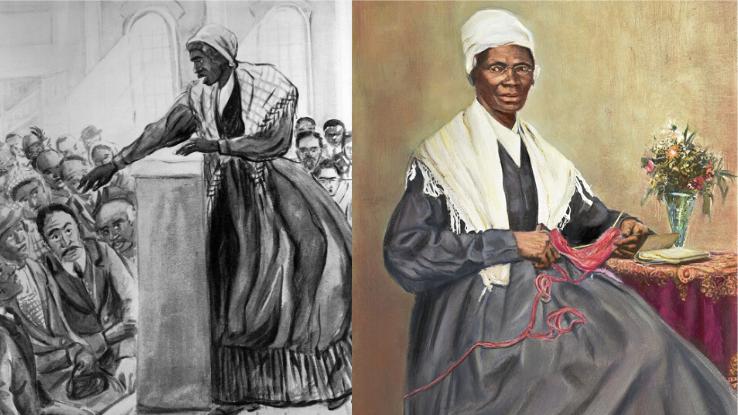

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883)

Born a slave, Sojourner Truth went on to become an influential orator, abolitionist and women’s rights advocate. After being sold four times and having five children while in slavery, Truth (originally named Isabella Bomfree) escaped in 1826 with her infant daughter and was taken in by the abolitionist Van Wagener family in New York. With the aid of the Van Wageners, Truth sued her former slave owner for custody of her 5-year-old son and won, marking the first successful lawsuit brought by a Black woman against a white man in U.S. history.

After gaining her freedom, Truth honed her public speaking skills working at religious revivals in New York. After meeting abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass in Massachusetts in 1844, Truth started giving speeches advocating for an end to slavery and for Black suffrage.

In 1851 Truth gave a speech at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention titled “Ain’t I a Woman?”. In it, she spoke powerfully about injustice, repeatedly using the rhetorical question “Ain’t I a woman?” to highlight the differences in society’s treatment of white and Black women.

Dorothy Height (1912-2010)

Dorothy Height was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1912. Growing up, Height attended racially integrated schools, excelling academically. After being turned away from Barnard College after being initially accepted, Height, undeterred, went on to earn a bachelor’s in education and a master’s degree in psychology from New York University.

After graduating from NYU, Height went on to work at the YWCA, where she became a leader within the organization and fought to end segregation within YWCA programs and facilities. During this time, she also met Mary McLeod Bethune and became involved with Bethune’s organization, the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). Height went on to become the fourth president of the NCNW.

Through her career, Height gained a reputation as a standout political organizer and expert on the issues driving the civil rights movement. Her reputation led political leaders, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower and Lyndon B. Johnson, to seek Height’s counsel and advice on political and racial issues.

After participating in the March on Washington in 1963, Height renewed her commitment to advocating for women’s rights, after noting that the male leaders of the event “were happy to include women in the human family, but there was no question as to who headed the household.” This led to Height working side-by-side with Shirley Chisholm, Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan to form the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971.

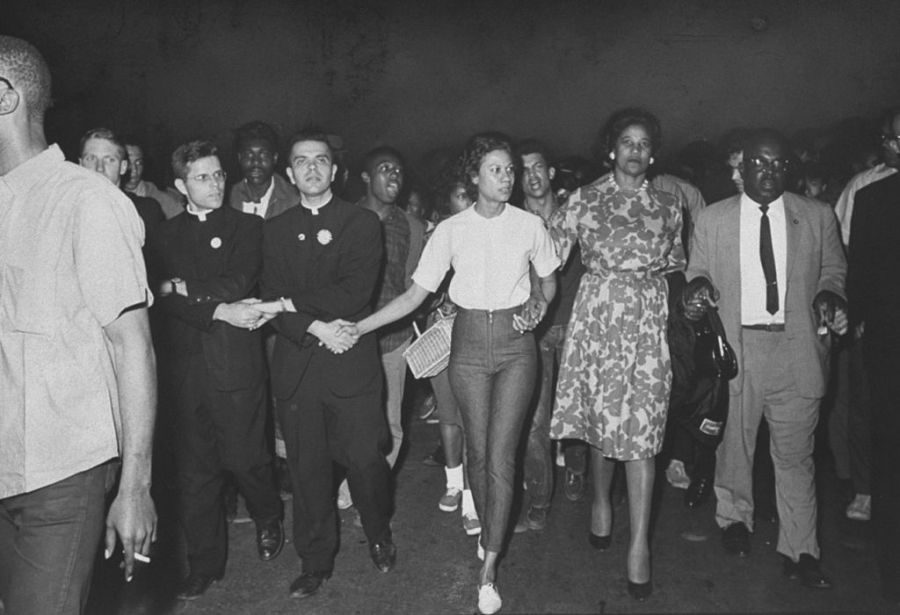

Gloria Richardson (1922-2021)

Richardson was born in Maryland in 1922 to an affluent family. Herbert M. St. Clair, Richardson’s grandfather, owned a funeral parlor, butcher shop and grocery store in the suburb of Cambridge, Maryland. Richardson attended Howard University at the age of 16, graduating in 1942 with a degree in sociology.

In 1962, Richardson became the head of the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC), and used her platform to advocate for an end to segregation in Cambridge, better health care for Black citizens, and an end to housing and employment discrimination.

Protests and campaigns in Maryland led by CNAC under Richardson’s leadership differed from those in the South in a few key ways. Richardson was never able to fully embrace nonviolence as a guiding principle, making the protests she led more volatile. In 1963, the Governor of Maryland, J. Millard Tawes, reacted to a confrontational CNAC protest by deploying the National Guard to the city to disperse the protestors.

Her Maryland protests also caught the attention of the federal government in Washington. In 1963, Attorney General Robert Kennedy proposed legislation called the “Treaty of Cambridge,” which would desegregate schools, provide more public housing, and allow the public to vote on a measure to desegregate public facilities. Richardson angrily rejected the treaty due to the proposed required desegregation vote, saying “A first-class citizen does not beg for freedom. A first-class citizen does not plead to the white power structure to give him something that the whites have no power to give or take away. Human rights are human rights, not white rights.”

Rosa Parks (1913-2005)

Known as the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” Rosa Parks is best known for refusing to give up her seat for a white man on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama in 1961. While this incident is key to the history of the civil rights movement, it was far from Parks’ first action against the injustice she faced as a Black woman in the South.

Rosa Parks, along with her husband Raymond Parks, was active in the struggle for civil rights in Montgomery starting from a young age. At 19, Parks joined the Montgomery Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and was eventually elected as the organization’s secretary. Parks worked for many years with the NAACP to fight for justice for Black citizens who were assaulted, murdered, and suffered violence at the hands of law enforcement. About this work, Parks stated, “We didn’t seem to have too many successes. It was more a matter of trying to challenge the powers that be, and to let it be known that we did not wish to continue being second-class citizens.”

Parks’ 1961 arrest after she refused to give up her seat on the Montgomery bus was a powerful catalyst for change. She worked with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to create the Montgomery Improvement Association, which organized a boycott of the bus company. Ultimately, the boycott and protests that accompanied it led to the desegregation of public transportation in Montgomery.

Daisy Bates (1914 -1999)

Daisy Bates experienced a tragedy early in her life that shaped and solidified her adult commitment to civil rights activism. When Bates was just three years old, her mother was killed in an act of racially-motivated violence committed by three white men. As a result, Bates grew up in the foster care system in Huttig, Arkansas.

In 1941 Bates and her husband, journalist Lucious Christopher “L.C.” Bates, started the Arkansas State Press, a weekly activist newspaper. The paper was one of the first of its kind, and Bates used it as a tool to spread awareness about and champion civil rights activism in Arkansas, including reporting on the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954 and the resulting struggle to desegregate Arkansas schools.

In 1957 Bates organized to support the Little Rock Nine, the first group of Black high school students to attend the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Bates let the students stay in her home, advocated for local government for their right to attend the school, and accompanied the students to the school on their first day, September 25, 1957. Bates retained a close relationship with many of the students for years after, supporting them through harassment and threats from opponents of desegregation.