Was the Underground Railroad Really Underground?

When you first hear about the Underground Railroad, it’s easy to imagine stations and subways in a system of tunnels below a city. When learning about the Underground Railroad, a lesser-discussed fact is that railroads weren’t underground until The London Underground opened in 1863. This might prompt you to wonder if any part of the Underground Railroad was really underground.

The Underground Railroad was more of a network than a place. It was formed and run by abolitionists — people who, during the Railroad’s time, supported the abolishment of the institution of slavery. Many of the abolitionists were former slaves themselves. While some historians may refer to the abolitionists as “conductors,” trains didn’t play a major role in the freedom of enslaved people who utilized the Underground Railroad.

With no straightforward methods of communication — no social media or even telephones — to facilitate organizing, and with no actual system of tunnels and tracks, it took innovative ideas to keep the Underground Railroad operating. Slavery eventually led the United States into its Civil War, and people needed to think and act carefully and resourcefully when helping enslaved people escape to freedom. Many formerly enslaved people, such as Harriet Tubman, risked their lives to do so. Come take a journey through the Underground Railroad — the real one — to find out more.

Editor’s Note: This article is a part of our ongoing American Myths series in which we explore the truths behind misrepresented people and events throughout history.

Secret Escape: Why the Underground Railroad Was Formed

The Underground Railroad was established sometime around the beginning of the 1800s. At this point in time, slavery had been codified into the United States Constitution. The Fugitive Slave Clause is located in Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution and was added in 1789. The Constitution was ratified in 1788, so it’s important to note that this was very much an issue the U.S. has had to reckon with since the country was formed. The clause made returning fugitive slaves a civic duty and meant that helping them escape was a federal crime.

A few years later, Congress reinforced this clause and passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Under the bill, enslaved people were considered property of their enslavers for the rest of their lives. Children born to enslaved parents were also considered their enslavers’ property. This act, along with the clause, fueled abolition — the push to end slavery — across the country, especially in the North.

The abolitionist movement has roots extending back to the 1600s. The Quakers, a Christian denomination known for their pacifist beliefs, vocally opposed slavery as the abolition movement gained speed. They were especially prominent in Pennsylvania, which in 1780 was the first state to outlaw slavery. Their early efforts extend back to 1688 with petitions that helped abolish slavery in every Northern state prior to 1804.

When enslaved people started to find freedom in the North, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed to impose further restrictions. This bill strengthened penalties for those who helped enslaved people escape and encouraged enslavers to track and hunt down those who ran away. The bill was nicknamed the “bloodhound bill” because dogs were used in these retrieval missions. The Fugitive Slave Act also caused outrage in the North and may have nudged the nation into the Civil War.

With the North and South so divided physically and ideologically, abolitionists had to put their thinking caps on to help slaves. Most enslaved people weren’t allowed access to education and were unable to read or write, so letters and maps wouldn’t have been effective communication tools for helping them escape. Instead, the solution involved new forms of communication that allowed freedom seekers to move along the real Underground Railroad: from safe house to safe house until they reached states where slavery had been banned.

Houses, Swamps, Voices: The True Locations of the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad wasn’t an actual railroad with trains and tunnels; the name is really just a metaphor. Instead, it was a network of secret routes that led to houses and properties where freedom-seeking former slaves could safely stay as they traveled to states where slavery had been abolished. But, like a railroad, it had stations, conductors and plenty of its own secret symbology.

Today, when asked to name someone that guides people on a journey towards a better life, you might call this person a “coyote.” Back in the days of the Underground Railroad, there were “agents” and “conductors.” An agent searched for plantations and locations with enslaved people, and a conductor guided the runaways between safe houses, which were called “stations” to conceal their true nature.

Since they couldn’t send letters or risk having discussions others might overhear, enslaved people communicated using the lyrics of songs and spirituals. These became signs that an agent or conductor was nearby or on their way. Harriet Tubman, one of the most famous conductors, was known for using the coded lyrics in songs to explain to enslaved people how they could escape or where they should go.

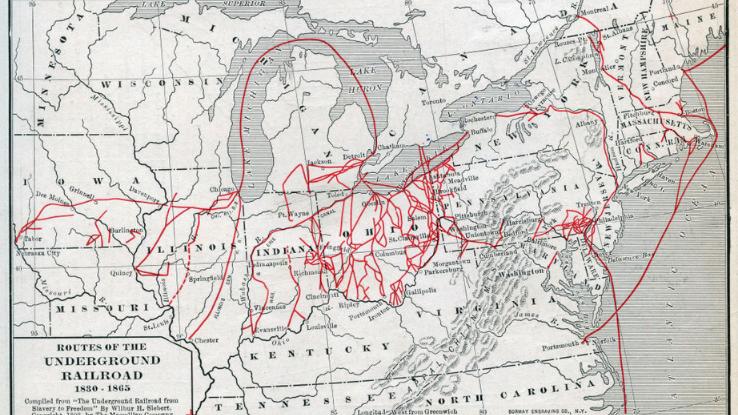

The National Park Service has compiled a list of 87 safe house locations that harbored “passengers” of the Underground Railroad. States that border Canada, like Ohio, New York and Pennsylvania, had more locations than non-border states. These refuges were mostly houses and churches — not tunnels or mines. In addition to the myth of the railroad being located underground, many are taught that these houses used coded quilts in windows to help people navigate different levels of safety during their travels. PBS and other outlets have debunked this, saying that enslaved people probably weren’t aware of the blankets’ meanings.

While people were on the run, they often didn’t have places where they could take refuge from those who were tracking escaped slaves. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increased the number of people hunting down escaped slaves. Areas like The Great Dismal Swamp, which is located in parts of Virginia and North Carolina, became imperative to the survival and freedom of runaways. Swamps and forests masked their scents, which helped people hide more effectively.

Because freed slaves in the North could be “claimed” by enslavers, Canada became the final destination for many newly free people. According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, between 30,000 and 40,000 people were able to find their freedom north of the border. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 contained a provision stating that if a slave made it to Canada, they would be free, but word of this didn’t spread until the War of 1812.

As more contemporary scholars and historians research this period of history, we’re learning that Canada was not the only haven for freedom seekers who escaped. Thanks to the work of people like Maria Esther Hammock, we now know that Mexico and Caribbean nations were just as important in helping enslaved people find freedom as Canada was.

Underground in a Social Sense? How the Myth Formed

So, how did the Underground Railroad become known as a vast network with tunnels and trapdoors? This has to do with the performative activism of white abolitionists. Wilbur Siebert, for example, was one of the first people to collect primary sources from formerly enslaved people and abolitionists.

The main criticism of Siebert and people like him is that they focused on the narratives told by white people rather than the folks who actually escaped. Larry Gara’s The Liberty Line was the first text to take on Siebert’s assertions. For example, Siebert reported 3,200 white male agents had helped run the Underground Railroad. Gara chose to focus on the narratives from formerly enslaved people who said that they escaped without help.

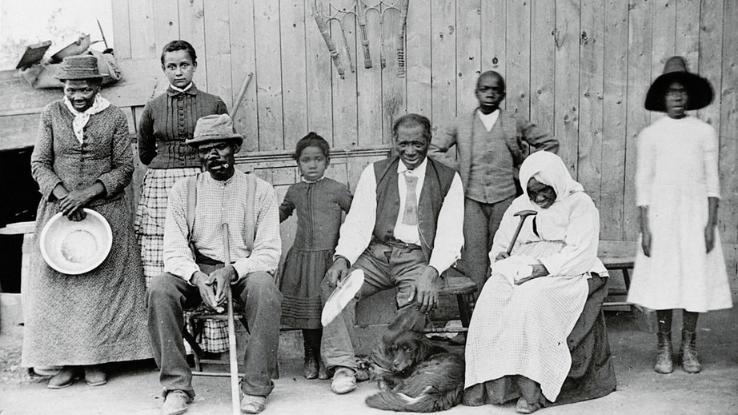

In, Gateway to Freedom, Eric Foner depicts a more accurate representation of the Underground Railroad. Foner had access to newly digitized testimonies from formerly enslaved people. These make it clearer that some white abolitionists were using hyperbole to describe the event. Foner points out, like in the photo of enslaved people on the run at the top of this article, that the Underground Railroad escapes took place in broad daylight, not necessarily at night like we’ve been led to believe.

Abolitionists, to spread the word, talked up their efforts on pamphlets and at rallies. This is perhaps the modern equivalent of posting an incriminating photo of someone on social media that could get them fired or arrested. Many abolitionists held bake sales and other fundraising events to help promote the cause. Black activists like Harriet Tubman, Levi Coffin, Thomas Garrett, Charles Torrey and Calvin Fairbank saved hundreds of slaves, but we mostly see Tubman in the history books. In history, sometimes only one figure from a movement is remembered, or at least named. Figures like Susan B. Anthony and Pocahontas received similar treatment in history books.

Many of the slaves interviewed said that they escaped with no help whatsoever, but their narrative was not chosen to represent this period of history. By 1860, three years prior to the Emancipation Proclamation, 3.9 million Black Americans were still enslaved — compared to 434,495 freed people. The abolitionist movement was important, as was the Underground Railroad — but their true stories aren’t always what we’re first told.

Bottom Line: The Underground Railroad Was Not Underground

Was the Underground Railroad actually underground? In a physical sense, the “railroad” was above ground. In a cultural sense, much of the escaping took place in broad daylight while abolitionists publicly applauded themselves. The Underground Railroad was not underground in any sense of the word.

For a more accurate representation of what it was like to “ride” the Underground Railroad, we suggest reading freedom narratives. In doing so, you will be doing what Siebert could not: putting the voices of formerly enslaved people at the forefront of the narrative. Books like Mary Prince’s The History of Mary Prince and Life of William Grimes: Runaway Slave by William Grimes provide more authentic depictions of the realities enslaved people were facing. Doing this type of work might help you become more “woke,” but what’s even better is that it can help break down invisible walls that might be keeping you apart from others.