What Went Wrong in Seattle’s Capitol Hill Organized Protest?

Seattle’s Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP) was, at least for a time, a police-free area. As people shared food and other resources and built a community focused on mutual support, it seemed like something new and powerful might be born out of gathering. However, after an outbreak of gun violence caused by people who were seemingly unassociated with the protests, Seattle’s mayor sent the police in to shut down the CHOP. What happened?

What Went Down in Seattle’s CHOP?

When protestors began to gather in the Capitol Hill area in late May and early June, there wasn’t initially a plan to create a social project as ambitious as the CHOP. Even so, the gathering quickly gained steam, with the Seattle Police Department’s East Precinct becoming a hotspot for protestor activity. While police used tear gas and pepper balls on anyone who approached the station, the decision was made to abandon the precinct on June 8. It was soon rechristened the “Seattle People Department” and adorned with a banner that read, “This space is now property of the Seattle people.”

A sign was put up declaring the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone. While the name was eventually replaced with the CHOP to keep the focus on Black lives and make clear that it wasn’t an independence movement, the idea that the protest could model a better world without police took off. Protestors created volunteer medic stations, held late-night games and film screenings and opened a “market” for free clothing, food and other goods. They also painted murals and worked to keep the streets of the CHOP clean.

However, even then there were signs that the protests were being co-opted. While the movement had started as a means for fighting for Black lives and rights, as it grew, people with other goals moved into the CHOP. An early example is when an unknown person or persons converted a basketball court into a vegetable garden, dirtying the entire area in the process. “When did Black people say they needed more vegetables?” asked several protestors interviewed by CNN.

Emergency Services Refuse to Enter the CHOP

Seattle police were unsupportive of the CHOP since its inception, with incidents like the alleged macing of a seven-year-old child and officers who covered their badge numbers before committing acts of violence causing friction with protestors. After the police withdrew from the CHOP, protestors did not encourage them to return.

The protestors managed their own affairs when violence broke out in the CHOP. However, there were times when they were unable to maintain order. On June 7, a man who opposed the protest drove his car into a large group of people and shot one person before surrendering to police outside the CHOP. In the early morning of June 20, things took an even worse turn when another protestor, Lorenzo Anderson, was shot and left in critical condition. When other protestors tried to call 911, they were informed that the ambulance wouldn’t enter the CHOP. The protestors agreed to carry Anderson outside the CHOP, but the ambulance also refused to meet them there because the police refused to declare the situation safe for medical personnel. The protestors then took Anderson to the hospital themselves, but by then it was too late: Anderson died of his wounds.

The rising violence combined with the arrival of newcomers who weren’t focused on the protest’s original purpose changed the atmosphere of the CHOP. Gang violence, possibly attracted to the CHOP by the lack of law enforcement and free use of drugs, reportedly began to become a problem. Many protestors, including volunteer nurses and doctors, left the CHOP as a result. While the protestors had armed guards that referred to themselves as Sentinels, they were unprepared for the situation they found themselves in.

The End of the CHOP

More protestors were shot by unknown assailants in the day that followed. After a rumor spread that the Sentinels themselves were going to be targeted, most of the protestors’ security forces went back to their homes. Despite protesting police violence, people in the CHOP found themselves having to cooperate with police homicide detectives to find out who was behind the attacks.

By the time the police moved in to end the CHOP on July 1, most protestors had gone home. Many of the remaining people were homeless and living in tents. More than 40 people were arrested as the police moved in.

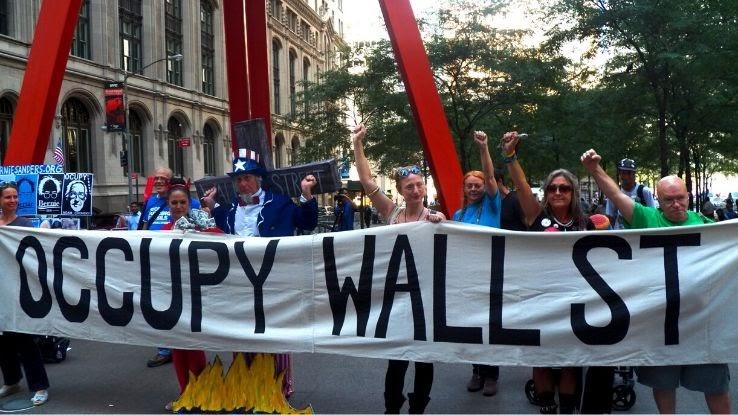

Comparisons to the Occupy Movement

Beginning in the fall of 2011, the Occupy movement became a global rallying call for economic equality. Protesters set up camp across nearly 1000 cities worldwide, and like the people of the CHOP, they attempted to provide services for each other and model a better society while demanding change.

In some ways, the CHOP was very different from the Occupy movement. While Occupy protestors had difficulty establishing specific policy demands, the CHOP’s were quite clear: a 50 percent cut in funding for police, the reinvestment of those funds into Black communities and amnesty for arrested protestors.

At the same, like Occupy, the CHOP suffered from not always having clear leadership. The number of divergent opinions on subjects such as Black-only spaces also hurt the unity of the movement. The openness of the movement also made it easy for other people to use it for their own purposes, whether that was other political goals, gang violence or just partying.

Legacy of the CHOP

Although the CHOP is gone, it’s hardly been forgotten. While Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan took little action against police brutality during the original protests and continues to resist calls to decrease police funding, she has agreed to the protection of murals created by the Black Lives Matter movement during the protests and made statements that could signal support for other actions.

More importantly, the CHOP helped protestors form stronger ties that they can use in further efforts to advance racial equality and end police brutality. Organizations like The Seattle Black Collective Voice and “Pay the Fee” Tiny Library (a free lending library that aims to share literature by people of color and LGBTQ authors) have already emerged as a result of the CHOP.

Protests also continue across the country, and activists continue to launch new initiatives to raise awareness about police violence and racism. While the CHOP may be gone for good, it continues to affect the renewed call for civil rights in the country.