What Is “Classified” Information — and Why Does It Matter?

After the FBI first performed a search of former President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home in Florida in search of classified documents, the news world began buzzing. Days later, the story broke that Trump had retained multiple sets of highly sensitive government records for personal use. But while there’s been ample coverage of the unfolding news and subsequent investigation, what hasn’t always been entirely clear to the general public is what “classified” means in this context. If you’re in search of some insights, take a look into the basics of classified information, including what it is and why it’s important.

How Classified Information Relates to National Security

In the simplest sense, classified information — also referred to as classified national security information — is any document or data stored through various means that contains intelligence the U.S. government has deemed sensitive. Essentially, if the data’s release to the public or certain unauthorized parties could pose a threat to national security, it’s considered classified.

Information is classified when it could create a potential threat to national security if the data got into the wrong hands. Broadly speaking, that means the data could be used to harm the country in some way. For example, certain details about the U.S. nuclear program could be damaging if other nations got ahold of them and used them for nefarious purposes. Details about military personnel — including their locations, planned movements or personally identifiable information (PII) — that could allow others to target them are also dangerous in the wrong hands.

Overall, specific types of documents and data are deemed potentially hazardous if unauthorized parties have access to the information. Here’s a quick list of various kinds of documents and data that are typically considered classifiable:

- Cryptology and cybersecurity practices, systems and safeguards

- Foreign government information and foreign activities in the United States

- Intelligence on various entities, sources and gathering strategies

- Military operations, movements, personnel data, plans and weaponry

- Nuclear program details, including locations of materials, current capabilities and facilities data

- Scientific, technological and economic matters that can impact national security

- System capabilities, project plans and vulnerabilities

Even if documents or data don’t fall under these umbrellas, they’re still eligible for classification. Anything deemed by various government authorities to pose a potential risk may be classified to ensure national security.

How Is Information Categorized?

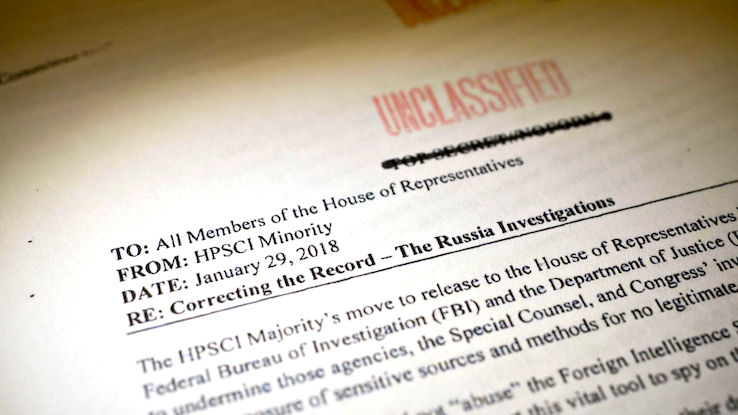

Classified information generally falls into three categories: confidential, secret and top secret. These classifications represent different degrees of risk.

While confidential information could harm national security if it were used improperly, secret information is data that would likely cause “serious” damage if it were released to unauthorized individuals. Top secret information poses the greatest risk. It has the ability to cause “exceptionally grave damage” to national security if it’s released to or viewed by unauthorized parties.

There are also some nuanced classifications that alter the ways classified materials of specific natures must be handled. One example is the Critical Nuclear Weapon Design Information designation, which is added to an existing secret or top secret designation and requires those with permission to view it to follow stricter rules regarding access and release.

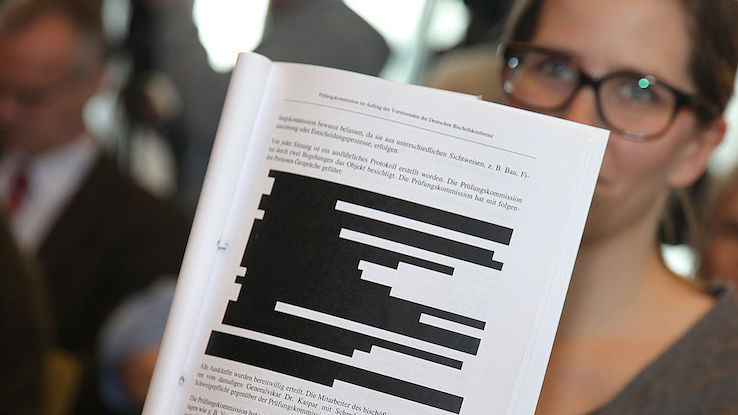

Once data is classified, this designation is typically physically marked on the material. For example, there may be “C,” “S” or “TS” markers on documents or individual paragraphs within documents. This makes it easy for those handling the information to know whether it’s classified and to ensure that classified portions are removed or redacted if the rest of the document needs to be viewed by a party without full and proper clearance.

There are several laws and regulations that govern the classification and handling of classified materials, including the:

- Atomic Energy Act

- Classified Information Procedures Act

- Espionage Act

Additionally, Executive Order 13526 applies. However, other mandates or laws may also be applicable to specific situations. These depend on whether mishandling occurred, along with other actions taken by individuals relating to the collection and distribution of the information.

What Are Security Clearances?

Security clearances are formal designations that determine when an individual is eligible to review classified national security information. People who have a security clearance undergo rigorous background checks that determine whether they represent a potential security threat. Only those who are deemed highly unlikely to reveal classified information to others can qualify.

As with document classifications, there are three primary levels of security clearances: confidential, secret and top secret. Those correspond with the data classifications, effectively outlining which levels a person can review. With a clearance, someone can view data at their level or with lower designations (as long as there’s a legitimate need). However, they aren’t approved to view documents at a higher level than their designation, regardless of the proposed reason.

Who Can Classify or Declassify Information, and When Can They Do It?

The ability to classify documents and data is governed by Executive Order 13526: Classified National Security Information, which was enacted by President Barack Obama. It grants the following individuals or groups the authority to classify information:

- President

- Vice President

- Agency Heads

- Officials Designated by the President

- Officials Designated by Agency Heads

Additionally, the executive order requires that subordinates only have access to classified information that they genuinely require in order to do their job, regardless of their security clearance.

Once a document is classified, a date is set for declassification based on the assumption that any related national security threat will have passed by that time. When that date passes, the data is declassified automatically. However, there are exceptions to that rule, such as with documents that may reveal certain confidential sources or specific details about particular weapons.

If a date can’t be identified, automatic declassification is set at either 10 or 25 years, depending on the overall sensitivity of the data. There’s no option for keeping documents or information classified indefinitely.

There are also processes for declassifying information before the timeframes elapse — a point that’s drawn attention in the wake of the FBI raid on Mar-a-Lago. In a statement, Donald Trump’s team claimed that the documents in Trump’s possession had been declassified by the former president.

Technically, a president does have the authority to declassify information under specific circumstances. Certain other government officials also have that capability. However, simply saying that the data is now declassified isn’t sufficient. There’s a complex process someone must follow to declassify information. Failing to follow it means that the information wasn’t formally declassified.

It’s also important to note that certain data isn’t eligible for declassification by a president. Mainly, that applies to information that falls under the Atomic Energy Act. Even an active president cannot choose to declassify those materials.If someone illegally possesses or otherwise mishandles classified information, there are potential penalties. If it’s deemed accidental, the penalty may be an administrative matter. However, if it’s intentional, per federal law (18 US Code § 1924), a person could face fines, up to five years in prison — or both.