What Role Should Police Play in a Democratic Society?

The voice of the people — at least the majority of the people — reigns supreme in a democratic society, so the people in that democracy should obviously have a say in the role of a segment as essential as the police. We rely on the police to maintain law and order and keep citizens safe. In a perfect society, that is exactly what would happen, but society isn’t perfect, and that isn’t always the end result.

Many people think incidents involving police brutality and excessive force are the natural consequence of a degenerating society plagued with unresolved social and racial inequalities and other problems. Maybe that’s true to some extent, but it’s also possible the problem could be rooted in behaviors and practices that date back to the beginning of policing in America. To understand what that means, let’s take a look at the history of the police in the U.S.

Colonial Night Watch

Although social order has always been a core component of civilized society, actual police forces haven’t always been the authority behind that control. Historically speaking, police officers are a relatively modern invention. In the earliest days of Colonial America, most towns relied on a simple system of night watchmen to prevent crime and watch out for trouble. Night watches were established as early as 1636 in Boston and 1658 in New York, mostly for the purpose of watching for nonviolent crimes like gambling and prostitution.

The men in the towns were obligated to participate in night watches, but many didn’t want to do it and didn’t take the task seriously. Some were even guilty of drinking or falling asleep while on duty. Wealthy residents frequently paid others to serve on the night watch in their place, and those they paid were often (ironically) criminals themselves. In some cases, serving on the night watch was assigned as a punishment.

Southern Slave Patrols

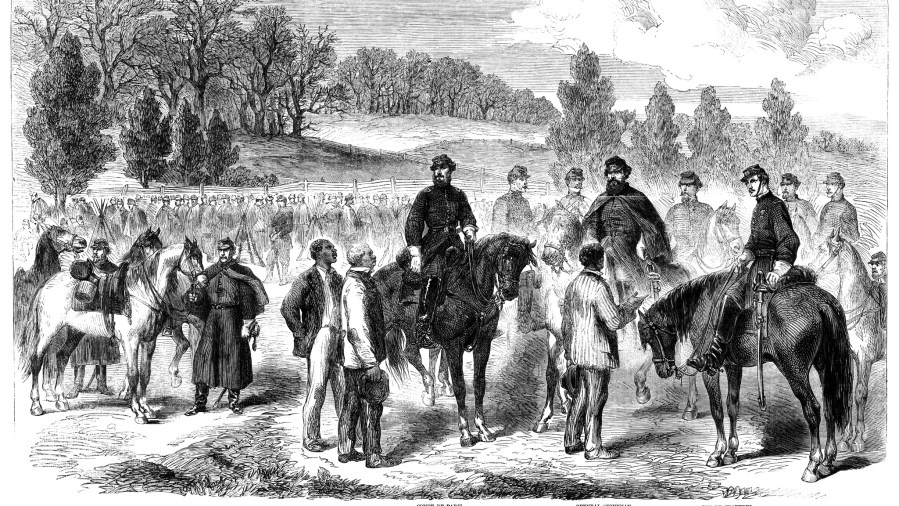

Early America was built on the idea of exploiting different kinds of labor. For people who settled in cities and towns in the North, it involved exploiting immigrants and the poor. For those in the South, it meant relying on slave labor. While night watches dominated in the North, slave owners in the South drove the birth of the Southern police system by creating slave patrols to enforce laws. The patrols consisted of three to six white men armed with whips and guns.

The first slave patrol was formed in the Carolina colonies in 1704 for the purpose of tracking runaway slaves and returning them to their owners. The patrolmen also used terror tactics to intimidate slaves and prevent revolts. Following the Civil War, these groups largely transitioned into police organizations that focused intensely on controlling freed slaves by enforcing segregation laws or vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan, who operated with the sole purpose of threatening, injuring and even killing Black people and other minorities like Native Americans.

Almost all white men had to serve on slave patrols, whether they owned slaves or not. Unfortunately, this practice created a sense of responsibility in white people that it was their duty to monitor the lives and movements of Black people. Additionally, the concept of treating enslaved people like they were property created the false illusion that white people had the right to inflict physical punishment.

Birth of the Organized Police Force

As cities began to grow larger throughout the states, night watch systems couldn’t handle the increasing sizes. In the northern states, merchants and other types of businessmen recognized the need for a solution and settled on an idea that would take the cost of security off their shoulders and make it a public expense. As a result, the first official organized police force began operating in Boston in 1838. Similar organizations started in New York City in 1845, Albany and Chicago in 1851, New Orleans and Cincinnati in 1853, Philadelphia in 1855, and Newark and Baltimore in 1857.

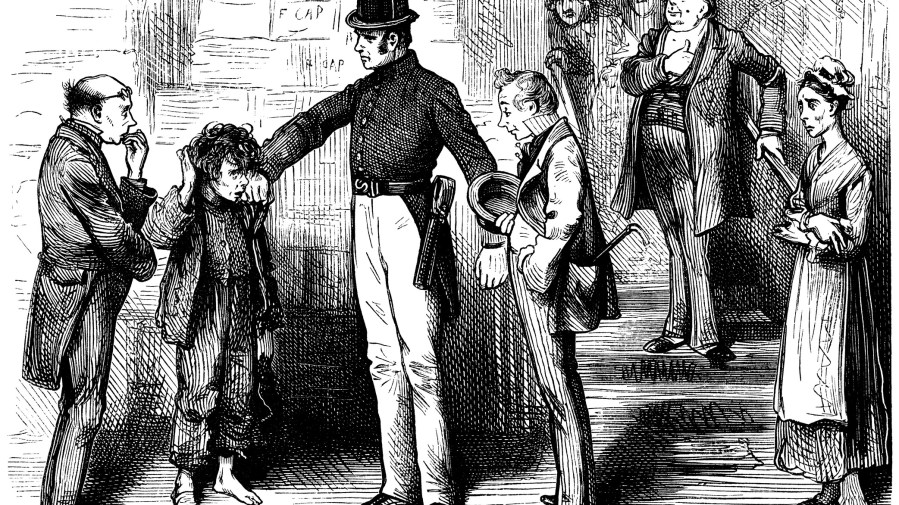

Early police forces had a few things in common with modern police, such as relying on public (city) funding to pay full-time officers who weren’t volunteers, but they were mostly different from what we see today. Immigrants continued to pour into the country, and many of those immigrants — Germans, Irish, Eastern Europeans, etc. — clashed with citizens who had mostly British and Dutch origins. Crime rates started to rise, and newly created police forces were tasked with putting a stop to it — with violence, if necessary.

The most powerful, wealthiest Americans controlled the actions of the police and directed them to keep immigrants, minorities and even poor white people downtrodden and “in their place” by criminalizing very minor transgressions and resorting to abuse. Their main duties should have been preventing crime and maintaining order, but they were politically and economically motivated to keep the social hierarchy intact instead. Ultimately, all the types of early policing in the U.S. were established based on two elements: controlling slaves and controlling minorities.

Rise of the Political Era of Policing (Mid-1800s to Early 1900s)

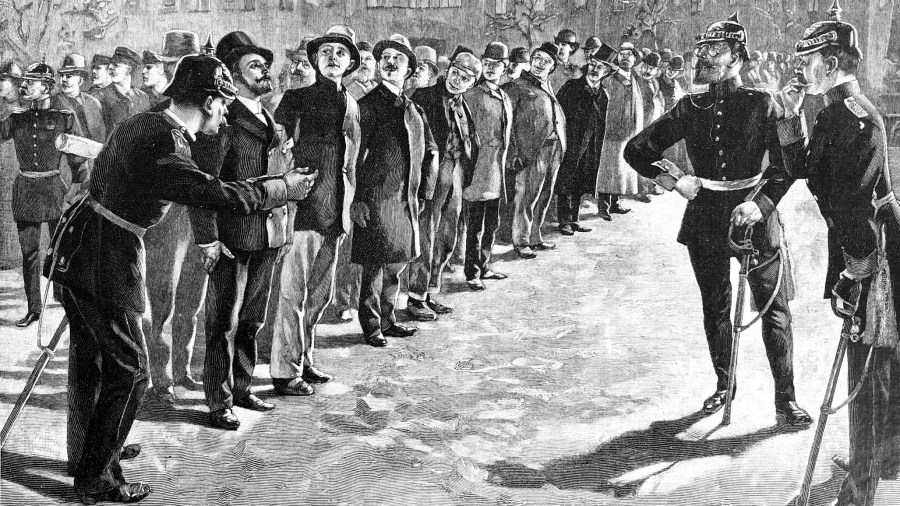

During the Civil War, the military served as the primary form of law enforcement in the South, followed by sheriffs during the Reconstruction period. The sheriffs were appointed by governors, primarily to maintain law and order in less populated areas. Most were corrupt and focused more of their attention on maintaining segregation than law and order. In the cities, police forces became increasingly common, but policing was strongly tied to politics at the time. The concept of maintaining law and order usually depended on the self-interests of the most powerful individuals in the city, who determined what “order” should look like. Local political leaders often selected police leaders, and bribes and payoffs were common.

Detective units that focused on investigating crimes first started to appear in police departments in the 1850s. Allan Pinkerton’s famous group of private detectives rose to fame during this period as professionals who put a stop to train robberies and union strikes. City police officers also actively focused on preventing strikes after the Civil War to preserve the financial interests of wealthy business owners, and they had no qualms about using brutal methods to force demonstrators to stop.

In the post-Civil War era, the wealthy upper class and merchants promoted the concept of “dangerous classes” of people. These classes consisted of everyone the elite viewed as inferior, which was generally poor whites, immigrants and free Blacks. Instead of following logical standards of reacting to crime, police officers began to focus on preventing crime from ever happening by scrutinizing the dangerous classes.

During this time, alarm boxes allowed business owners to alert police officers, and patrol wagons started being used to transport large numbers of people arrested all at once, often those who were striking or protesting. Merchants pressured police officers to wear uniforms to make them easier to spot in crowds, a practice that still exists today. Police officers began carrying firearms during this period, even before they were officially granted permission to arm themselves.

By the early 1900s, state police agencies started to appear, mostly to further control workers by enforcing “public order” laws. As a whole, police departments supported specific political allies and persecuted and arrested political enemies. Politicians were behind much of the original types of organized crime, such as gambling, racketeering and prostitution, and at the turn of the 20th century, police forces were little more than enforcers for organized crime.

Rise of the Reform Era of Policing (Early 1900s to 1960s)

At the close of the 19th century, city police officers mostly focused on policing the poor and ethnic groups deemed potentially dangerous by the elite and wealthy members of society who were in charge. During what is known as the Great Migration, large numbers of Blacks left the South and rural areas and moved to large cities. As Black city populations grew, the idea persisted that Blacks were a dangerous class and needed to be monitored — sometimes to the point of harassment — more than white people.

In the early 1900s, August Vollmer — often called the “father of modern policing” — recognized the problems with American policing and developed a comprehensive plan to reform the system. His approach mostly focused on incorporating social work and psychology into policing. He also created a separate judicial system for juveniles and promoted the creation of state and federal police forces to cope with Prohibition violations and the rise of organized crime. Motivated by Vollmer, police forces began to move toward more professional codes of conduct based on much more respectable behavior.

Attempts at reform sometimes involved investigative commissions that were established to focus on specific types of criminal activities within police departments. In New York City, the Lenox Committee (1894) was one of the earliest examples and focused on police extortion related to prostitution. The Curren Committee (1913) also focused on police ties to prostitution as well as gambling, while the Seabury Committee (1932) turned its attention to corruption related to Prohibition (1919-1933), a period when speakeasies frequently popped up in major cities, and officers took bribes to ignore them.

On a national scale, President Herbert Hoover created the Wickersham Commission in 1929 to investigate illegal activities and issues with police forces all across the country. The commission also conducted the first investigation into organized crime in America. Other prominent cities that established commissions to spearhead broad investigations during this period included Philadelphia, New Orleans, San Francisco, Atlanta and Los Angeles.

Attempts were also made to reform police departments by installing new leadership and implementing a testing system for promotions within a police department. Departments established specific selection standards and training requirements and incorporated civil service tasks into the job description. The end result was a system with more bureaucracy and a clear chain of command. The new system separated police from politicians and created special squads for certain types of crimes, such as narcotics, vice, investigations and traffic.

Landmark court cases during this period also forced specific reforms on police departments by dictating the way certain processes had to be legally handled. Due process was first addressed in Mapp v. Ohio in 1961, when a judge laid down strict rules to prevent illegal searches and seizures in criminal cases. In Escobedo v. Illinois in 1964, the judge determined a suspect is entitled to an attorney, and any statements made without an attorney aren’t admissible in court. Possibly the most well-known case, Miranda v. Arizona in 1966, dictates that a suspect must be informed of all rights before they can be questioned.

Police Professionalism Movement (1950s to 1970s)

At the end of the Reform Era, a movement known as police professionalism took hold in many police departments across the country. O.W. Wilson first established the concepts of police professionalism in the 1950s. The movement promotes military-style organization with a centralized command unit and pushed for the added reach of motorized patrols instead of foot patrols.

Unfortunately, many of the newly adopted procedures led to resentment of the police in many communities, partially due to racial profiling that targeted minorities as potential criminals without cause. Officers isolated themselves from the public and were resistant to complaints and criticism. By the mid-1960s, police unions were created to protect officers. Most police departments in large cities had a police union by the early 1970s. In addition to protecting officers, unions implemented coercion tactics like “blue flu” and work slowdowns to demand things like pay raises and equipment upgrades.

The “Taylorization” of the police — terminology borrowed from the factory industry related to optimization — involved downsizing police forces and focusing on job specialization. Patrols went from two officers in a car to one, and new technology, such as the 911 system, was implemented to help officers do their jobs. Some of the more mundane jobs were passed off to civilians to complete. Unfortunately, some of the measures meant to improve their capabilities actually widened the divide between police officers and the public.

The relationship became even more strained when police departments used force to control protesters during the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War protests. Many situations got out of hand, and instead of protecting the peace, police officers became a common source of social tension. Throughout the 1960s, Blacks and minorities began to protest police treatment itself, engaging in everything from peaceful protests, boycotts and sit-ins to out-of-control riots, and the police response was often harsh and violent.

In 1969, the Stonewall riots lasted six days when the LGBTQ community fought back after a police raid of Stonewall Inn in New York City. This event ultimately led to the Gay Rights Movement. By the mid-1970s, the country was largely dissatisfied with policing and distrustful of police officers. To make matters worse, research studies in the late 1960s and early 1970s showed that police patrols didn’t prevent crime, and assigning detectives to work cases didn’t improve rates for solving crimes.

Diversity among police officers remained rare during this period as well, with women only accounting for approximately 2% of officers in 1970 and racial or ethnic minorities accounting for less than 10%. Those numbers did eventually improve to 13% women and 25% minorities in 2017.

Rise of the Community Problem-Solving Era of Policing (1970s to Present)

In the 1970s, police administrators began to recognize that police officers deal with many behaviors that aren’t criminal, such as psychological behaviors and social issues. As a result, they began to focus on ways to address those problems and turn police officers into allies instead of adversaries. Gradually, they initiated community policing strategies that called on communities to work in conjunction with the police to control crime and solve other community problems, including those related to social issues and mental health.

The goal of community policing is to decentralize the police so officers can establish positive relationships with their communities. If trying to control crime through a police presence and intimidation was unsuccessful, then they believed collaboration and trust could be the answer. The idea is that it’s far too difficult to control crime and maintain order without a strong connection to the community.

Community policing uses resources to solve problems rather than just respond to problems as they happen. By the early 21st century, two-thirds of local police departments relied on community policing strategies around the country for dealing with common local crimes and civic duties. Additionally, new specialty divisions were created as new threats appeared. The 1999 Columbine school shooting triggered the development of new, more effective processes for handling mass shootings, for example.

In 2001, the 9/11 terrorist attacks led to the establishment of highly skilled counterterrorism units. Unfortunately, the heightened level of diligence combined with the trauma also led to increased racial profiling in some communities. After 9/11, the number of accusations regarding police brutality, excessive force and racial profiling started to increase once again. Some highly publicized deaths led some departments to start using body cameras, but body cameras don’t always seem to influence behavior when tensions run high.

Finding a Way Forward

Casting officers in roles that make them part of the community is a positive move that has taken police departments as a whole in the right direction, but problems still occur at times that result in face-offs between the police and the public. Lingering racist ways of thinking about crime that date back to the early days of policing in America could be partially to blame. If training for officers still includes elements of race, religion or social class when learning how to spot suspicious actions or a potentially dangerous person, then the training protocols certainly need to change immediately.

Additionally, modern police budgets eat up all the funds that could go to services needed to help society, which could in turn reduce the number of people committing crimes and going to jail. More money spent on social programs versus policing could reduce harm to citizens as a whole. This is what most people have in mind when they call for a move to defund the police. Most people don’t want to eliminate the police force; they want to refocus some of the money to fund social and mental health programs to better handle individuals who create disorder but aren’t criminals.

Protests all over America demand change at the least or even the elimination of the police force at the most extreme. Speaking out against acts of police brutality is our right and our social responsibility, but the situation becomes more complicated when those protests lead to riots, vandalism, arson and other crimes that require police intervention for the protection of bystanders, business owners and property. When you look at the history of the police in the U.S., it’s clear that the police have come a long way and improved dramatically in the past four centuries, but that doesn’t mean they have fully evolved to what we need them to be. We can only hope the recent protests ultimately lead to the continued evolution that will keep moving policing in a positive direction.