Why Is Literature Important and Why Do We Study It?

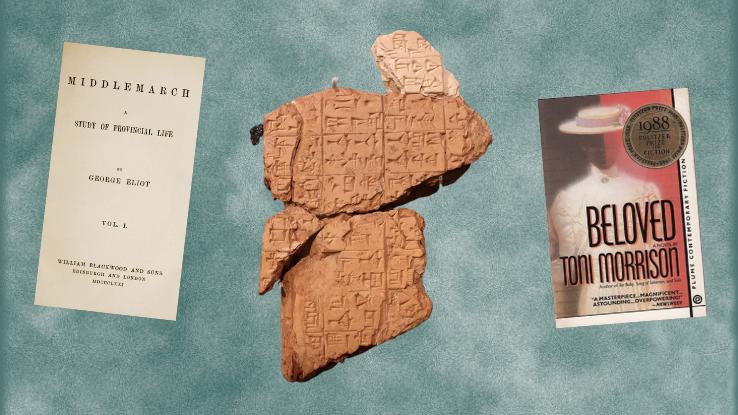

For many folks, the word “literature” conjures up memories of high school English class reading lists. While the Western literary canon is expanding to include, and elevate, stories outside of what white, Western readers have dubbed “the classics,” there are still some works that crop up in every student’s career, from Frankenstein and the Epic of Gilgamesh to Beloved and The Great Gatsby. So, why is literature important — and why do we study it?

Merriam-Webster defines literature as poetry or prose that has “excellence of form or expression and expressing ideas of permanent or universal interest.” While it may sound trite to say, the world’s greatest works of literature have changed minds, sparked rebellions, and helped to alter the course of history. While it would be impossible to contain all of literature’s contributions and multitudes here, we’re going to take a look at some of the landmark moments in this art form’s history.

Literature Transports Us To the Past

Like other recovered art objects, literature has the power to tell us about ancient civilizations. Not only can we understand their customs, values and lives, but we can get a better idea of what their entertainment looked like. The first-known examples of literature can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamia. Around 3400 BCE, the Sumerians developed a system of writing called cuneiform, which allowed scribes to record myths, hymns and poetry. Some of these earliest-known transcriptions include the “Kesh Temple Hymn” and the “Instructions of Shuruppak,” both of which were written around 2500 BCE.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, a long-form Mesopotamian poem, was originally written around 2100 BCE. Even today, Gilgamesh is considered the first great masterpiece of world literature. In fact, much of the Bible parallels this ancient work, furthering emphasizing just how universal and influential Gilgamesh was — and continues to be today.

In 375 BCE, Plato, the Athenian philosopher, authored The Republic, a dialogue between Socrates and his fellow Greek thinkers, which explores thought-provoking questions about justice, order and the just man. And, around the 8th century BCE, the landmark epics attributed to the poet Homer, The Odyssey and The Iliad, helped preserve Greek mythology and history in writing.

Literature Helps Us Reevaluate Our Worlds

Early on, literature was contained within poetry and dramatic works — after all, performing plays was another great source of entertainment. During the 11th century, or the Heian period, Japanese noblewoman and lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu penned The Tale of Genji, which is considered the first modern novel by many scholars.

Years later, in Europe, things started to shift in a meaningful way in the wake of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, a collection of 24 stories written in Middle English between 1387 and 1400. Picking up the prose torch around 1485, Thomas Malory published Le Morte d’Arthur, one of the first novels in the Western canon. During the Renaissance, writers like Molière began satirizing everything from the church and government to society at large, showing that written works had the propensity to shift the balance of power and make people rethink their world views.

During the 16th century, also known as the Ming dynasty, the Chinese novel Journey to the West was published. Attributed to Wu Cheng’en, this satire- and allegory-filled work is considered one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature. Around the same time, William Shakespeare was helping to lay the foundations of modern English and craft the literary tropes and story formats we still enjoy today. And, of course, in 1615 Miguel de Cervantes penned Don Quixote, a romantic, archetypal novel that’s considered one of the most influential works of all time.

Literature Gives Folks a Voice and Platform — and Let’s Readers See Themselves Reflected

Again, it’s impossible to fully encapsulate the breadth of literary history here. Moreover, this article focuses on written works, but it’s important to note that many cultures and groups of people record stories through imagery instead — or pass their stories down in oral traditions. All of this to say, our view of literature is a narrow one, and, in many ways, limited by the way educational institutions have shaped our understanding of what works are important.

James Simpson, head of Harvard University’s English Department, spoke about these limitations directly in an open letter to the Wall Street Journal entitled “Great Literature Magnifies Repressed Voices, Always.” For Simpson, the ages-old Western literary canon, which highlights the literary contributions of white (and often straight) men, “betray[s] the fundamental function of literature and other art forms, which is to hear the voices repressed by official forms of a given culture.”

Of course, the literary canon has been refreshed in past, which proves that it’s important to reshape and rethink the stories we deem essential. For example, at the time of its writing Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter was kind of the scandalous (easily consumable) HBO-like story of the day. But, now, it’s largely considered a probing, essential work — not just entertainment. In the wake of World War I, authors like Virginia Woolf and F. Scott Fitzgerald penned novels, like Mrs. Dalloway and The Great Gatsby respectively, that captured their disillusionment first and foremost. However, these continue to be must-read works due to the way they exemplify craft and storytelling elements. (At least in part.)

More modern literature also ushered in the more formal notion of literary sub-genres, ranging from science fiction — a genre created by Frankenstein author Mary Shelley — to romance, fantasy, and realism. By retracing certain tropes, conventions and character types, genre helps us understand the way particular stories are shaped by categorizing them.

Without a doubt, literature helps us uncover — be it an uncovering of the past, a present self, or a possible future. The most distinguished literary greats, like Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Margaret Atwood, James Baldwin, Kazuo Ishiguro, Chinua Achebe, Jhumpa Lahiri, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Zadie Smith, and Maggie Nelson (and many, many more folks we don’t have the space to name!), capture all of these facets. In short, by climbing into the minds of other characters and worlds — in stepping outside of ourselves — literature allows us to understand universal truths; change minds; stir empathy; and express our identities and values in lasting, far-reaching ways.