From Pandemics to Protests, Here’s How Global Events Transform Our Vocabularies

It’s no secret that the coronavirus pandemic has changed the world as we knew it, reshaping everything from our social lives to our economies. Since the onset of COVID-19’s global spread, the ways we socialize have changed. Offices are closed, faces are covered, restaurant booths have caution tape on them — the list goes on. The pandemic is changing more than how we act, however. COVID-19 is also changing the ways we think and speak, and languages across the globe are experiencing these shifts.

In Germany, 1,200 new words have recently come into usage due to the pandemic. English-speaking countries have all added new words to their respective dictionaries, too. With all this chaos going on, many of us are now asking where new words come from and what types of events have an impact on language — whether it’s English or any other tongue.

How COVID-19 Created 1,200 New German Words

Behind every word, there is a story. That story can stem from whatever the word is describing, the person or people who created it or a large-scale event that surrounded it. The COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, has been changing the ways we communicate — and will do so for the foreseeable future.

The Leibniz Institute for the German Language is the premier institution for researching and documenting the German language. So far, it has reported 1,200 neologisms that have arisen because of COVID-19. Most of these new words are compounds, words formed by a primary word and a determiner. A determiner is a word that modifies a noun but isn’t necessarily an adjective. So, words like “the” or “every” are popular determiners because they tell a lot about a noun without being too wordy.

For example, “coronafrisur,” which means “lockdown hairstyle,” is made up of “corona” and the German word for “hairstylist.” “Impftragheit” means “vaccine sluggishness” and is made up from “impft,” the word for “vaccinate,” and “inertia.”

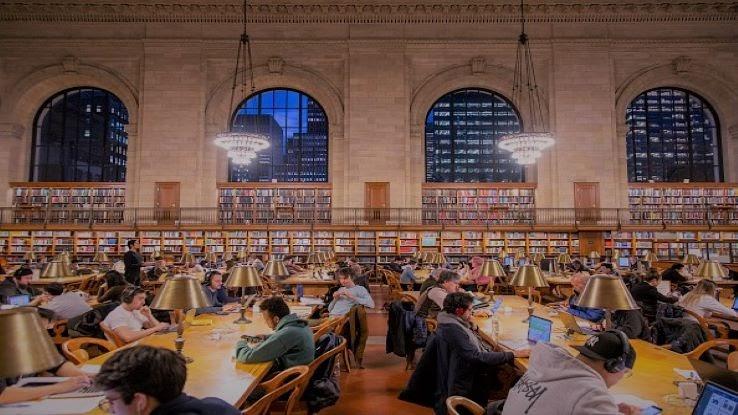

Over in English, The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) noted that most lexical innovation in 2020 happened because of the pandemic. Its editors added more than 2,100 new and updated words to the dictionary last year. We have our own fun terms, like “doomscrolling” and “covidiot,” two more compound words. The dictionary that’s a bit of a grandparental figure for the English language typically shares four major updates a year — one per quarter — but 2020 brought unprecedented behavior from everyone, including Oxford. In July, the dictionary’s announcement essentially said that libraries’ and other academic facilities’ shutdowns slowed a lot of linguistic progress that’s typical for the development of Standard English. This process for standardizing words can be long — but fun to look at from afar.

What Is a Neologism? Ways of Becoming a Word

“Neologism” is a fancy term for a new word. People form new words all the time, sometimes without thinking about it. Sometimes a new word is onomatopoeia, an eponym or a borrowing from another language, and sometimes it’s the fusion of two words. A new word we use when speaking English won’t necessarily be Standard English — a word or phrase recognized by major drivers in linguistics like the OED or Webster’s Dictionary.

As ever, there are many paths a neologism can take in becoming a word, phrase or updated definition for a word. Dictionary.com’s main criteria is that the linguistics in question need to be used widely and for a long time. Merriam-Webster boasts a more data-driven approach. A global pandemic is the perfect example of a lingual catalyst — a phenomenal event that has a rapid impact on a language.

There are many paths on the road to becoming a word. Global pandemics and other large-scale events impact more than our economy and the outside world: disasters can also change the way one person or how an entire country speaks. If every word has its own type of story, there are thousands of events like this that alter and shape our language over shorter and longer periods of time. The following examples illustrate the ways five other events change and alter language, English or otherwise.

Colonialism and Conflict: Words of War

New words and language may not be the first things that come to mind when the subject of war and conflict comes up, but it is more pleasant to think about language than the violence that comes along with it. Wars of words won’t lead to many linguistic alterations, but when people from different places are engaging in physical conflict, it results in lingual crossovers and sometimes the eradication of an entire language. Norman French was the national language of England, for example, but English has gone on to become a language that many considered one of the most colonial languages in known history.

World War I was particularly notable in terms of its impact on language. Spanish, Hungarian, French, English, Russian, Portuguese, Chinese, Thai, Greek, Romanian and Dutch are just a handful of the languages spoken among the 32 nations involved in this global conflict. It might be a surprise to learn that the term ‘”cushy” originally comes from soldiers describing “easier” missions, and its root word is “khush,” an Urdu word for “pleasure.”

The Great War also made way for medical terminology like “cooties” and “crummy.” Pilots had their very own language to innovate, interacting with new technologies on the fly and engaging in battle. The sounds of all of these new words needed describing, so “pipsqueak,” “whizz-bang” and a personal favorite, “dud,” entered our language. The United States also made the error of referring to Serbia as “Servia,” which the small nation wasn’t too happy about.

Technology: Describing Innovations

New tech and other inventions often result in a snowball of language; invented objects need names. Sometimes that means naming a product after its inventor, which was the driving force behind words like jacuzzi, Graham cracker, Ferris wheel and the George Foreman grill.

After the thing is named, there are often new adjectives and verbs to describe the technology or its purpose. These terms can vary by region and other circles. Some people say, “Put the SpaghettiOs in the microwave, please,” but others say “nuke it” or “zap it,” for example. Other words like “sedan” or “SUV” further clarify what we imagine when someone’s describing a car.

The internet’s rise to ubiquitous levels tackled language to the ground and changed communication forever, too. Written communication’s new digital accessibility resulted in a lot of change. Yes, there were new words, like “website,” “inbox” and “email.” Online diction has led to abbreviations like “omg” and “lol,” new verbs like “texting” and “surfing the web,” and adjectives with new uses like “digital” and “online.” Social media, the internet’s sometimes-demonic child, has piggybacked off this, with terms like “tweeting,” “blogging” and “selfie” leaving our lips in new and exciting ways.

Beautiful Minds: How Art Affects Language

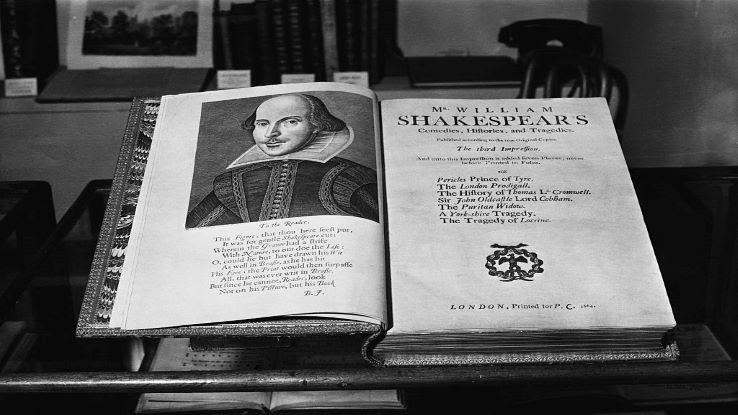

William Shakespeare was born in 1564. He added over 1,700 words to the English dictionary. While there aren’t many Shakespeares in this day and age, art impacts language — a lot of our language — on a daily basis. When it comes to new words and language that appear in art, new words are often either invented or borrowed from another language.

Examples of a borrowing include Americans’ increasing use of the phrases “livin’ la vida loca,” following the rise of Ricky Martin’s hit song from the ’90s, and “señorita,” which, despite being a commonly used Spanish word, peaked in online searches in 2019 according to Google Trends — just after the Shawn Mendes and Camilla Cabello song of the same name topped the charts.

Examples of word invention can be found in a lot of science fiction, fantasy and speculative fiction as well. In exploring unknown worlds, it takes an artist to create something new — including words. While writing 1984, for example, George Orwell created terms such as “doublethink” and “Big Brother,” both of which are still used today. Words like “telescreen,” which perfectly describes a smartphone or tablet, and “speakwrite,” which describes talk-to-text technology, didn’t quite stick, so language can sometimes seem like a matter of chance.

Some folks like J.R.R. Tolkien and George R. R. Martin have gone as far as creating their own languages for their worlds. The Star Wars franchise has introduced many terms and phrases, most notably “may the force be with you,” which has been used in presidential addresses.

Sometimes artists invent words by putting two together. This can be seen in Destiny’s Child’s “Bootylicious,” which was written by Rob Fusari, Beyoncé Knowles and Falonte Moore and added to the dictionary in 2004. There’s also “YOLO,” short for “you only live once,” which was popularized by Drake’s “The Motto” and was added to the OED in 2016.

Anything but the F-Word: Language of Censorship and Correctness

English speakers, especially in the United States, will hop through leaps and bounds to avoid saying a word that’s considered offensive. For language that’s referred to as “dirty” — or worse, “French” — a surprising amount of language is dedicated to the avoidance of these terms and phrases: Power Thesaurus boasts over 756 synonyms for the”F” word.

Mindfulness and social change can also contribute to linguistic changes and additions. Addressing political correctness, the late Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison said famously that much of it arises when those who have been named and defined by others start to name and define themselves. As a result, different groups of people are asking to be referred to by their preferred terms.

These conversations on the correct way to refer to a group of people are constantly evolving and mean more change. An example of this change is the shift in usage from Indian to Native American to Indigenous. Sometimes this results in a debate in which multiple parties’ reasonings are valid, like with the sometimes controversial term Latinx.

Social Change and Revolutionary Protest: The Power Is Yours

In 2020, the OED added terms like “structural racism” in response to the world watching unprecedented protests for social justice and equity take place. Folks at Oxford also modified the entry for the word “knee” to include the phrase “to take a knee” and provide context about Colin Kaepernick and the movement to raise awareness of structural racism.

The ultimate driving force of language is people. Yes, art, catastrophes, innovations and other game-changers can have an impact on our language, but at the end of the day, changes stem from you and the folks you keep around yourself.

If you’re looking to improve or diversify your vocabulary, you can always open a book or start a conversation with a friend or friendly stranger. We never have to stop learning new words. When the pandemic ends, we may have even more words for the mass gatherings, intense feelings of closeness to people and other situations we’ll be seeing through a COVID-tinted lens. So, whether you’re speaking from behind your mask or typing new words with your fingers, make sure you watch your tongue. You might be onto something.