We Explain the Complicated History of Myanmar and Aung San Suu Kyi

The path toward democracy in Myanmar — also called Burma — remains an unsteady one, marred by violent and often militaristic uprisings while the country has long struggled to find a secure political footing. Until very recently, Myanmar was subject to sanctions by the United States for what the U.S. deemed “undemocratic” government practices, and in the wake of recent political developments in the Southeast Asian nation, it appears that these restrictions will return. While Myanmar’s persecution of its Muslim minority population created a crisis giving rise to significant international concern, the country appeared to maintain its status as an emerging democracy. That is, until a military coup took place in February 2021 following an allegedly flawed November 2020 election. Here’s what you need to know about the complex crisis, including its fascinating history.

Where Is Myanmar, and Why Does It Have Multiple Names?

Myanmar is a Southeast Asian country of approximately 58 million people. Starting in the north and working around the compass, the country is surrounded by China, Laos, Thailand, the Andaman Sea, the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh and India. It has an area of approximately 261,219 square miles — just 7,000 square miles smaller than the state of Texas. Since 2006, Nay Pyi Taw has been the country’s capital city. The official name of Myanmar is the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, or Pyidaungsu Thamada Myanmar Naing Ngan Taw in Burmese.

Myanmar is also known as Burma. The country was called Burma until its name was changed to Myanmar in 1989 by a military government that laid down an edict called the Adaptation of Expression Law. The United Nations and many individual countries — but notably not the United States or the United Kingdom — officially recognized the nation by its new name, Myanmar. Those that continued to call the country “Burma” did so to avoid the appearance of legitimizing the military junta’s takeover. In any event, the word “Burmah,” as it once was spelled, is a local variation of the word “Myanmar.” Anthropologist Dr. Gustaaf Houtman, an expert in the country’s political culture, has described “Myanmar” as the name that’s “ceremonial and official and reeks of government,” while “Burma” is an “informal, everyday” term.

Who Is Aung San Suu Kyi?

Aung San Suu Kyi is the daughter of a famous Burmese military general, General Aung San, who devoted his life to pursuing the country’s independence from British rule. She studied philosophy, politics and economics at Oxford University before marrying an English academic and settling in the U.K. with her husband and children.

Suu Kyi returned to Myanmar in 1988 to care for her ill mother at a time when the country was in the midst of student-, worker- and monk-led protests seeking democratic reform. By August of 1988, she had become an active leader of the protests and of the revolutionary movement opposing the ruling military dictator General Ne Win. Citing her father’s efforts, she began traveling around the country to lead revolts and rallies while calling for “peaceful democratic reform and free elections.”

By this time, Suu Kyi had become a well-known revolutionary figure. The army sought to put a stop not only to rising support for the leader who was following in her father’s freedom-fighting footsteps but also to the democratic principles she was inspiring more and more people to demand. In September of 1988, the army took control of the country in a coup and eventually placed Suu Kyi under house arrest. By this time, however, a new political party — called the NLD, or the National League for Democracy — had begun taking shape under Suu Kyi’s leadership.

Then in 1990, the country’s military government held elections to appoint new leaders. Representing the NLD, Suu Kyi ran against, among dozens of other political parties and potential candidates, a former associate of General Ne Win named Sein Lwin. The NLD ultimately won the election in a landslide. However, the army refused to surrender and continued to imprison Suu Kyi intermittently over the course of two decades until November 2010.

By that time, Aung San Suu Kyi became one of the most prominent political prisoners on the planet, having spent 15 of the 21 years between July 1989 and November 2010 in prison. In 1991, she received the Nobel Peace Prize “for her non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights.”

In November 2010, Myanmar held its first elections in two decades and Suu Kyi was released from house arrest. In April 2012 by-elections, Suu Kyi’s party won 43 of 45 votes, and she became a member of Myanmar’s parliament in that election. In 2015, the NLD again won 86% of the seats in Myanmar’s parliament — another signal of clear support for democracy among the country’s voters.

Though Suu Kyi was the leader of the winning political party, she could not legally become president under Myanmar’s constitution because her (now deceased) husband and children were foreign citizens. Instead, she was given the newly created title of State Counsellor.

The Rohingya Crisis

Nearly 90% of Myanmar’s population practices Theravada Buddhism, and minority religions include Christianity, Hinduism, animism and Islam. Approximately 6% of Myanmar’s population is Muslim, including most of its Rohingya group — an ethnic minority that has lived for centuries in Myanmar but to whom the government refuses to grant citizenship.

Since 2017 — and while Suu Kyi has been State Counsellor — the Muslim Rohingya population in Myanmar has been subject to significant oppression, attacks and widespread killings, along with violent suppression by the army, which had forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya people to flee to neighboring Bangladesh. Myanmar is now subject to charges of genocide at the International Court of Justice and is undergoing investigation for crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court.

Myanmar’s mistreatment of the Rohingya people under the NLD government significantly undermined Suu Kyi’s once-widespread international support. Former supporters now accuse her of condoning genocide, rape, murder and other atrocities. While Suu Kyi maintains acclaim across Myanmar and was long seen as a human rights icon, many members of the worldwide political community now denounce her as “a global pariah at the head of a regime that has excused a genocide, jailed journalists and locked up critics” in a country that “remains as repressive as ever.”

The February 2021 Coup

In November of 2020, Myanmar’s national elections appeared to return the NLD to power with far more than the 322 seats required to lead the country’s government. Even before the official counting of all ballots was complete, however, the opposition party — supported by Myanmar’s army — protested that the vote was marred by irregularities and demanded a revote. The Union Solidarity and Development Party alleged that early voting results had demonstrated “errors of neglect” affecting voters’ lists and breaches of laws and procedures. Myanmar’s Union Election Commission, however, reported that the election was fair, free and transparent.

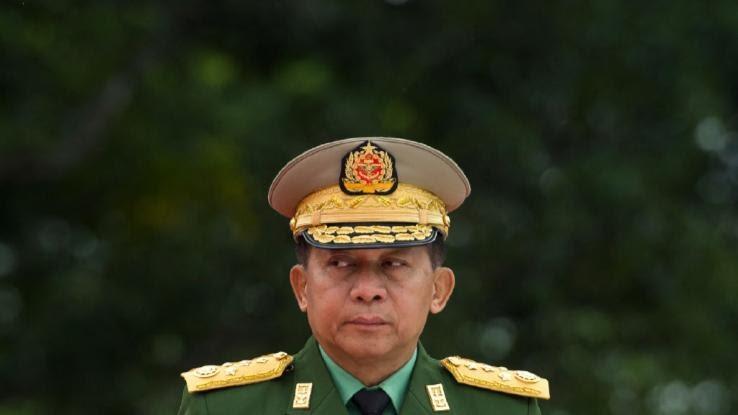

In response, on February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military leaders seized control of the country. Several leaders of the NLD — including Suu Kyi and President Win Myint — were arrested, and army general Min Aung Hlaing was installed as the de facto head of the government. According to announcements from the military, 24 government ministers and their deputies were removed from office and replaced — including ministers in key government departments relating to finance, foreign affairs, interior affairs and health. The army imposed a curfew, began patrolling Myanmar’s streets with troops and imposed a one-year-long state of emergency.

How Has the United States Responded to the Coup?

On February 1, 2021, the White House released a statement from President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. regarding the coup in Myanmar. President Biden referred to the military’s actions as “a direct assault on the country’s transition to democracy and the rule of law.” He encouraged the international community to unite to pressure the military to relinquish power and unsubtly threatened to reinstate former sanctions that had recently eased when it appeared Myanmar’s government was becoming increasingly democratic.

Just 10 days after lifting these sanctions, Biden announced a new set of restrictions on military leaders and other entities in Myanmar. These included actions to prevent individual military leaders from accessing as much as $1 billion in Myanmar government funds held in American bank accounts. Of the decision, Biden noted, “We’re also going to impose strong exports controls. We’re freezing U.S. assets that benefit the Burmese government, while maintaining our support for health care, civil society groups and other areas that benefit the people of Burma directly.”

Those statements come less than one month after Biden’s newly appointed Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced a plan to pursue an interagency review by the United States government. This review would investigate and determine whether Myanmar’s persecution of the minority Muslim Rohingya population constitutes genocide. Such a finding would certainly complicate the United States’ relationship with Myanmar and other countries in the region — a set of relationships that have become much more complicated since the November 2020 election and February 2021 coup in Myanmar. As the coup continues, it remains to be seen how or when Myanmar — and the international community — may see a resolution.