This ‘Extinct’ Giant Tortoise Was Just Confirmed Alive in the Galapagos

Princeton geneticists compared DNA from a tortoise specimen collected over a century ago on Fernandina Island, Ecuador, to identify the species.

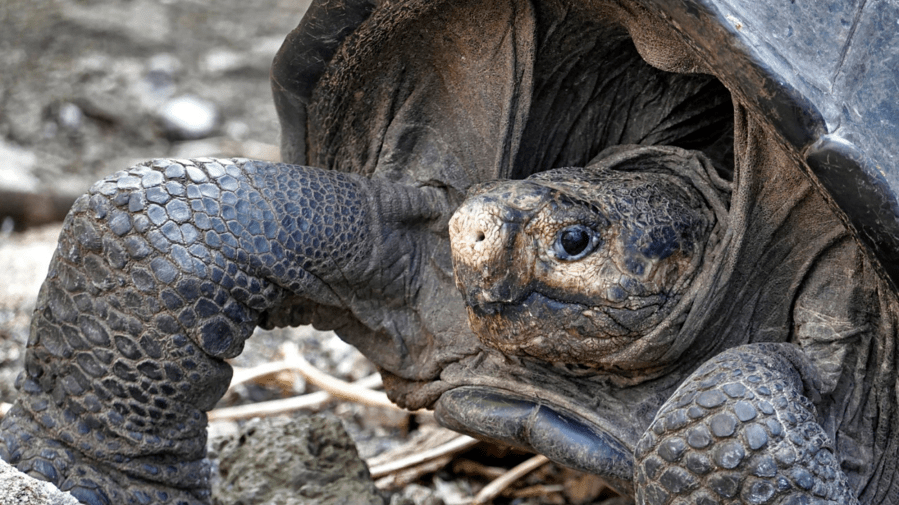

When a team of biologists discovered a lone tortoise within a small patch of vegetation on Fernandina Island’s jagged lava fields in 2019, they initially thought she’d been transported there from somewhere else. The female, eventually named Fernanda, lacked the saddleback flared shell characteristic of the only native tortoise to be discovered on the island until then — a male specimen collected by the California Academy of Sciences during a 1906 expedition.

Now, thanks to a paper published on June 9, 2022, in the journal Communications Biology, any doubts can be laid to rest. Princeton University’s Stephen Gaughran and colleagues sequenced the genomes of both Fernanda and the 1906 museum specimen, comparing them to the other known Galápagos giant tortoise species. The results confirmed that the two tortoises found on Fernandina Island over a century apart were not only genetically distinct from the others but were also members of the same species. The Fernandina Island Galápagos tortoise species was, in fact, not extinct.

A Fantastic Discovery

The study’s authors extracted DNA from the femur of the museum specimen, also known lovingly as the “fantastic giant tortoise,” which is currently preserved at the California Academy of Sciences collection. Scientists previously believed the Chelonoidis phantasticus to have died out more than a century ago, making the museum tortoise the last known individual of the species — what’s referred to in science as an “endling.”

They sequenced the DNA at the Yale Center for Genomic Analysis along with a small sample of Fernanda’s blood. The process was approved by Yale’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which ensures the humane care and use of animals involved in research initiatives.

“Like many people, my initial suspicion was that this was not a native tortoise of Fernandina Island,” said Gaughran in a press release. “We saw — honestly, to my surprise — that Fernanda was very similar to the one that they found on that island more than 100 years ago, and both of those were very different from all of the other islands’ tortoises.” Gaughran is a postdoctoral research fellow in ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton, where he also works in deciphering seal and walrus evolution.

Galápagos Giant Tortoises

Tortoises are believed to have been carried by storm from the South American mainland westward to the Galápagos Islands about two or three million years ago. It was also common for mariners to move them between islands as food sources before they were federally protected. Over time, the tortoises evolved into 14 distinct species, now ranging from vulnerable, endangered, critically endangered or extinct on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. Lonesome George, the last known survivor of the now-extinct Pinta Island tortoise species, became a conservation icon before his death in 2012.

“The discovery informs us about rare species that may persist in isolated places for a long time,” said Peter Grant, Princeton professor of ecology and evolutionary biology who spent over 40 years studying evolution in the Galápagos. “This information is important for conservation. It spurs biologists to search harder for the last few individuals of a population to bring them back from the brink of extinction.”

Giant tortoises were exploited both for their oil and meat during the 18th and 19th centuries by pirates, whalers and fur sealers. During the same period, endemic rats and other rodents brought to the islands by ships preyed on tortoise eggs and hatchlings, which also devastated populations. Those two centuries saw a loss of between 100,000 to 200,000 tortoises, with just 20,000 to 25,000 wild tortoises living on the islands today.

Tortoises help shape their ecosystems by dispersing plant seeds throughout their range. Although they’re certainly not known for their speed, studies have shown that giant tortoises are the most important seed dispersers when it comes to frequency of dispersal in the Galápagos.

What’s Next for Fernanda?

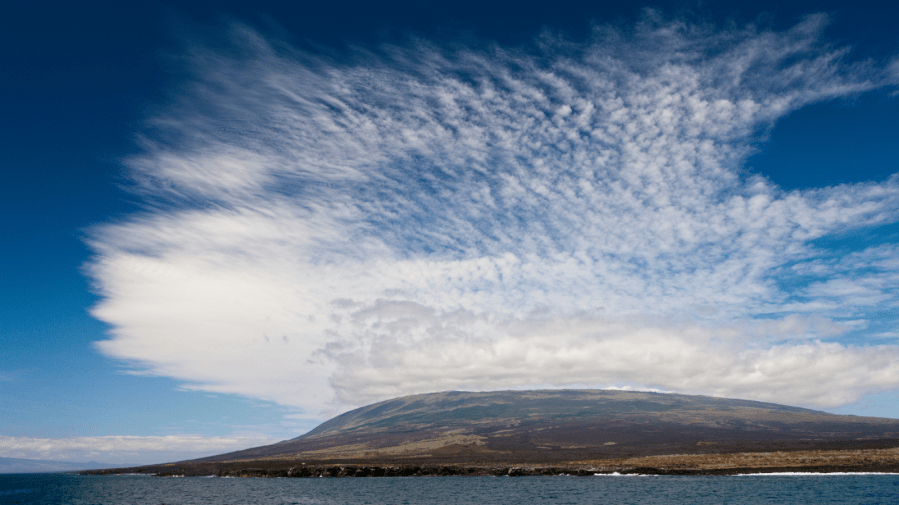

According to the study, researchers have observed tracks and scats belonging to at least two to three tortoises on other expeditions to the island, which is known for its highly active volcanic eruptions (the most recent of which occurred in 2005 and 2009). At just under two feet long and over 50 years old, Fernanda’s growth was likely stunted and her features distorted due to her isolation on the northwestern flank of the volcano — cut off from the main vegetated areas by several lava flows.

Today, Fernanda is living in comfort and safety at the Galápagos National Park Tortoise Center, a rescue and breeding facility on nearby Santa Cruz Island. “She likes to eat cactus as well as other plant species, and is healthy and very active each morning,” said Director of the Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative, Wacho Tapia, who wrote about being present for Fernanda’s discovery in 2019.

The volcanic landscape on Fernandina Island makes expeditions difficult — likely what made it possible for Fernanda to go so long without being noticed. Ideally, if a male tortoise could be found he could be introduced to Fernanda at the National Park’s Giant Tortoise Breeding Center on Santa Cruz Island.

The next steps at that point would be overseeing breeding efforts in captivity and eventually returning them to safer habitats on their native island. Giant tortoise breeding programs have proven successful in the past. The Galápagos’ Española giant tortoises recovered from 12 females and three males in 1976 to a stable population of 2,000 tortoises in 2019, after which the 15 original breeding tortoises were returned to Española Island. A far cry from the Fernandina Island species’ lone survivor in Fernanda, but hope remains that more of her species will be discovered in the future. Galápagos giant tortoises can live for over 100 years, after all.

“Whether Fernanda is the ‘endling’ of her species or not, she represents an exciting discovery that engenders hope that even long unseen species may yet survive,” wrote the study’s authors. “The future of the Fernandina tortoise species depends on the outcomes of further searches of this remote and difficult-to-explore island that could result in the discovery of yet more Fernandina tortoises.”