Monarch Butterflies Are Showing Signs of Recovery

Have you noticed a dwindling number of insects in your backyard, community garden or local park over the years?

Etymologists (people who study insects for a living) call it the “windshield phenomenon,” a reference to the anecdotal observation that there’s been fewer smashed bugs on car windshields since the early 2000s. This bleak picture of an “insect apocalypse” — which some scientists believe will result in the loss of over 40% of insect species within the next few decades — is believed to stem from the ever-so classic combination of habitat loss, invasive species, pollutants and climate change.

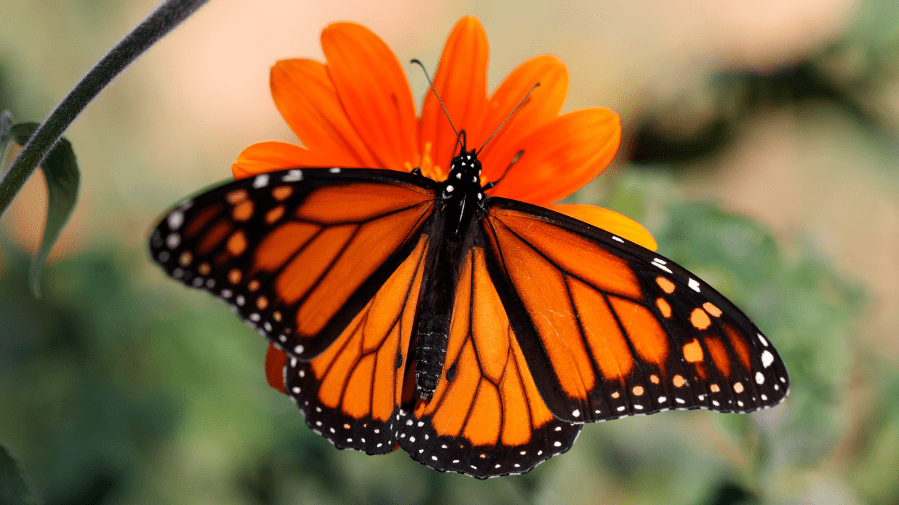

North America’s monarch butterflies, unfortunately, are no exception. These well-studied and brilliantly-colored insects have become somewhat of a poster child for the plight of our planet’s pollinators — and rightly so — as the western overwintering population has plummeted more than 99% since the 1980s.

Unsustainable pesticide use, climate change and the loss of pollinator plants have led to fluctuating monarch populations in recent years, but in 2022, there’s already been growing evidence that North American monarchs are showing significant signs of recovery. The iconic insect, it seems, may be on the path securing a more hopeful future.

Are Monarch Butterflies Endangered?

The monarch species as a whole (Danaus plexippus) is native to North and South America, but is now widely distributed throughout many different countries. Not all monarch populations make major migrations, and some don’t even migrate at all.

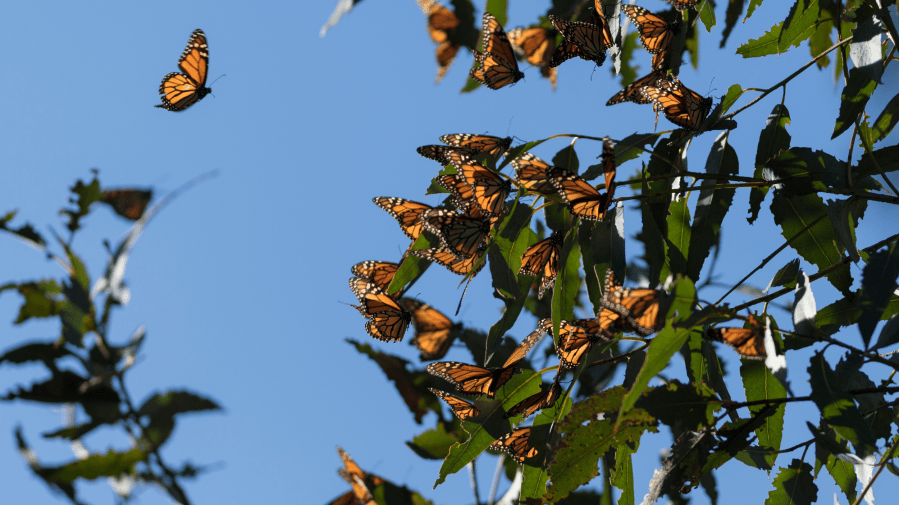

There are two distinct types of migratory monarchs in North America: the eastern population that travel from Canada to southwestern Mexico in the winter, and the western population that live west of the Rocky Mountains and overwinter along the California coast. Typically, the more disheartening narratives are referencing these North American monarch butterflies.

Since the 1980s, scientists have observed a downward trend in North American monarch numbers as they overwinter in Mexico and California. The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) estimates that the eastern population fell from about 384 million in 1996 to 14 million in 2013, though the population in 2019 rose to around 60 million. The western population decrease was more abrupt, from 1.2 million in 1997 to less than 30,000 in 2019.

By 2020, USFWS predicted the probability of the western population reaching the point of inevitable extinction to be as high as 68% within 10 years and 99% within 60 years. For the eastern population the chance of extinction in 60 years under current conditions ranged from 48% to 69%.

After western monarch numbers reached its record low, USFWS acknowledged that the subspecies met listing criteria under the Endangered Species Act, though the agency opted not to include the insect on the list in favor of other, “higher-priority” species. Today, the monarch remains a “candidate” for listing, meaning the agency will re-evaluate the subspecies in 2024.

Scientists Draw Surprising Conclusion in Monarch Study

On June 10, 2022, researchers from the University of Delaware and the University of Georgia (UGA) finalized the largest and most comprehensive assessment of the global breeding monarch population to date. Using data from volunteer citizen scientists from the North American Butterfly Association, they compiled over 135,000 butterfly observations in specific sites around the US and Canada between 1993 and 2018, looking for possible drivers of population patterns and changes.

Interestingly enough, the team found an overall annual increase in monarch abundance of 1.36% per year. This suggests that the breeding population in North America is not, on average, declining. Rather, migrations to Mexico or California may be getting more difficult due to factors like traffic, parasites and extreme weather events, resulting in fewer butterflies completing the journey. The catch is that they often compensate for those losses when they come back north to breed in the spring.

According to the study’s authors, this good news is a cautious one. As global temperatures continue to increase, so will the number and severity of threats to monarchs and other insects. What’s more, if the winter population of migrating monarchs gets low enough, they may lose their ability to recover altogether.

“There are some once widespread butterfly species that now are in trouble,” said William Snyder, co-author of the June 10th study and professor of entomology at UGA, in a press release. “So much attention is being paid to monarchs instead, and they seem to be in pretty good shape overall. It seems like a missed opportunity. We don’t want to give the idea that insect conservation isn’t important because it is. It’s just that maybe this one particular insect isn’t in nearly as much trouble as we thought.”

More Studies Spell Hope for Western Monarchs

According to the World Wildlife Fund’s (WWF) most recent survey of butterflies in Mexico, monarch numbers went up by 35% between 2021 and 2020, sparking more hope for the subspecies. The survey showed that the presence of monarch butterflies at the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a famous monarch butterfly sanctuary in Michoacán, Mexico, grew from 5.19 acres in December 2020 to 7.2 acres in December 2021. Although the population is known for its fluctuating numbers, they’ve been on a trending decline for years; In the winter of 1995-96, for example, monarchs covered a whopping 45 acres worth of forest.

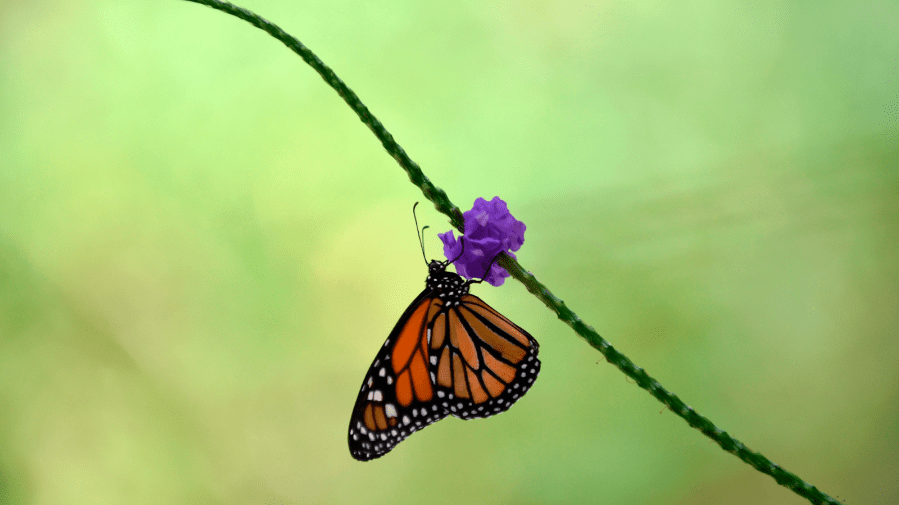

“The increase in monarch butterflies is good news and indicates that we should continue working to maintain and reinforce conservation measures by Mexico, the United Statesand Canada,” said Jorge Rickards, general manager of WWF Mexico. “Monarchs are important pollinators, and their migratory journey helps promote greater diversity of flowering plants, which benefits other species in natural ecosystems and contributes to the production of food for human consumption.”

The Xerces Society, an international nonprofit for the conservation of invertebrates and their habitats, has been organizing the Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count for decades. Though the community science program has documented a rapid decline of migratory monarchs during its time overall, the latest count tallied 247,237 butterflies — an over 100-fold increase from 2020’s total of 2,000 and the highest since 2016.

“We’re ecstatic with the results and hope this trend continues,” said Emma Pelton, the Western Monarch Lead for the Xerces Society. “There are so many environmental factors at play across their range that there’s no single cause or definitive answer for this year’s uptick, but hopefully it means we still have time to protect this species.”

How to Help Monarch Butterflies and Other Pollinators

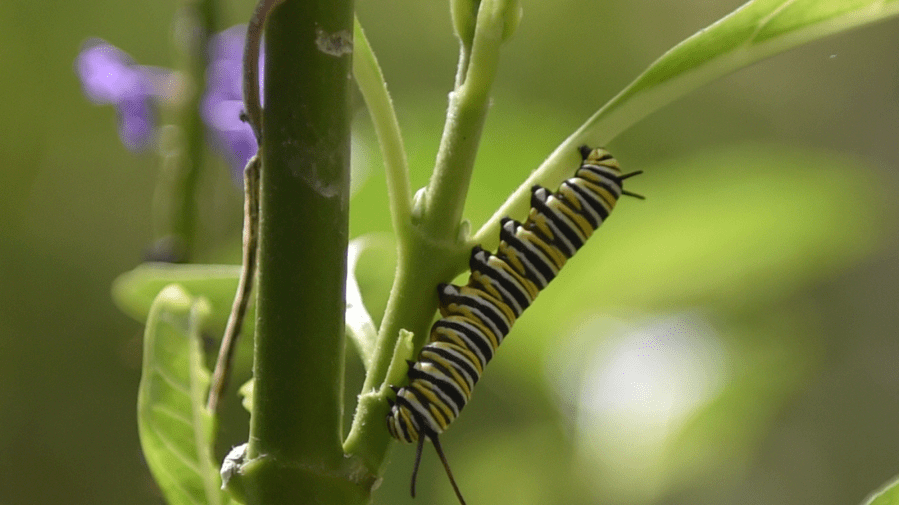

Planting native wildflowers that bloom in late summer to early fall can help feed and replenish butterflies as they make their migratory journeys. Look into organic gardening techniques that avoid adding insect-killing pesticides to your garden, as well. The National Wildlife Federation, the Xerces Society and the Monarch Joint Venture have partnered up to develop monarch-specific nectar plant guides for regions within the continental US. You can also plant native milkweed flowers, which monarch caterpillars need to grow and develop, or plant trees, which protect migrating monarchs at night or during severe weather.

Studies show that — in addition to planting pollinator-friendly plants in your garden — turning off your porch light could also help support monarch butterfly migration. Artificial, nighttime light pollution can interfere with a butterfly’s natural navigation abilities by interrupting their circadian rhythms.

Monarch butterflies are already a well-recognized and treasured insect, but greater awareness is still needed to save them. Sharing information about the importance of not just monarchs but all pollinators is key to securing the future of these vulnerable creatures and safeguarding our entire planet’s biodiversity.