Hitchin’ a 400-Legged Ride: Why Are Japanese Millipedes Halting Train Traffic?

For generations, people have waxed poetic about the romance of train travel, about seeing the countryside and setting off on a long journey to a new land. Alfred Hitchcock took a slightly different approach to riding the rails in the 1951 psychological thriller Strangers on a Train...and things perhaps devolved from there, eventually taking on a decidedly horror film-worthy twist in the mountains of Japan.

Today, the East Japan Railway Company and West Japan Railway Company operate several train lines connecting cities like Mitaka, Chiba, Hokuto, Nomoro, Shiga and Kanazawa. They typically run with the precision and punctuality that the country’s railways are known for providing. But even these expertly engineered, logistics-laden train lines aren’t immune to creepy crawlies. Back in 1920, a train traveling in the mountains west of Tokyo was forced to stop — not an unusual event in and of itself.

But the cause of the stoppage was strange: The tracks traversing the terrain were buried in mounds of millipedes, and this would soon become a regular occurrence. Now, scientists have finally learned why these multi-legged invaders periodically swarm Japanese train tracks, giving us fascinating insight into bug behaviors in the process. In honor of National Wildlife Day, we’d like to Japan’s fascinating relationship with millipedes.

First Things First: What Are Millipedes?

Millipedes are a group of arthropods with pairs of jointed legs on most segments of their multi-segmented bodies. A millipede typically has over 20 segments to its body, meaning these creatures have lots of legs. From its Latin root, the word “millipede” means “a thousand feet,” but that’s a bit of a misnomer; millipedes do have lots of feet, but there are no species that has 1,000 of them. The number of legs on a millipede ranges from about 40 to 400, depending on the species. Some types of millipedes are venomous — a quality that aids them in paralyzing their prey.

As if their physical appearance wasn’t strange enough, their initial arrival on train tracks in Japan puzzled the train crews working the newly opened line traversing the mountainside. The same phenomenon — mounds of ghostly white millipedes deep enough to block a train — began occurring every few years after long periods of dormancy. Exactly what was going on wasn’t understood until a century later thanks to a January 2021 report titled “Eight-year periodical outbreaks of the train millipede,” which was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

The type of millipedes capable of blocking trains in Japan is of the species Parafontaria laminata armigera — a type that’s now commonly referred to as the “train millipede.” Each train millipede is less than 1.5 inches long and is usually found in forests in Japan’s central mountains. As they age, they turn orange with a dark brown stripe and produce a scent similar to almonds as a defense mechanism. But that scent is more than just a nuisance; it’s actually a small amount of the poison cyanide being released. Cyanide production aside, millipedes play an important role in the forests’ ecosystems by digesting organic material and cycling nitrogen.

Did Mounds of Millipedes Really Block Trains?

The millipedes’ interference with train travel in Japan, which workers first noticed in 1920, occurred over and over again — several years apart — for a century before scientists fully understood just what was happening. The oldest records of millipede obstructions relayed events in 1920 and 1936, and subsequent incidents were recorded in 1976, 1984 and 2000.

How many millipedes appeared, exactly? In the Koumi Line incident that took place from August 1984 to July 1985, measurements found a density of 168 to 454 millipedes per square meter on the tracks. During the same period on nearby roads, a density of 768 millipedes per square meter was noted. On some occasions, train operators would simply wait for the piles of millipedes to cross the tracks. Other times, though, the blanket of millipedes needed to be cleared away before the train could continue along its route.

To better understand this bizarre occurrence, researchers Keiko Niijima, Momoka Nii and Jin Yoshimura conducted a multi-year research project into the phenomenon. Fortunately, government ecologist Keiko Niijima had already begun studying the millipedes back in 1974, and researcher Jin Yoshimura, a professor emeritus at Shizuoka University, had been conducting research on periodical cicadas for decades. This experience formed the foundation of their research, coming in handy both in the scientists’ initial formal investigation into the train millipedes and in later analysis for their study.

What Do Periodical Cicadas Have to Do With This Phenomenon?

“Cicadas” refers to a cluster of species that people often call locusts, but they’re actually different bugs. What’s fascinating about periodical cicadas is that they spend the first 13 or 17 years of their lives underground feeding on fluids they gather from the roots of trees in forests in eastern areas of the United States. After spending those first 13 or 17 years underground, the cicadas emerge in the spring in the form of mature cicada nymphs. The bugs show up in massive numbers — often extending into the millions in a specific geographic area — as they surface from their subterranean incubation.

Having spent 13 or 17 years — depending on their species — underground, those cicada nymphs live for just a few weeks above ground. Their primary purpose is to mate and lay eggs in woody plants before disappearing for another 13 to 17 years. That “period” of 13 to 17 years is what causes those cicadas to be called “periodical.” So, why do periodical cicadas have such a curious and fascinating life cycle? One theory is that they emerge only every 13 or 17 years to avoid appearing at the same time as some of their predators.

Until Niijima, Nii and Yoshimura conducted their investigation into Japan’s train millipedes, it was believed that seven species of cicadas were the only creatures with such a long periodical life cycle. (It’s important to note that lengthy periodical life cycles are known to exist in some plant species, including bamboo.) As it turns out, there’s at least one more creature with a many-years-long periodical life cycle that causes lapses in their above-ground existence: Parafontaria laminata armigera — Japan’s train millipede.

Train Millipedes Have an 8-Year Periodical Life Cycle

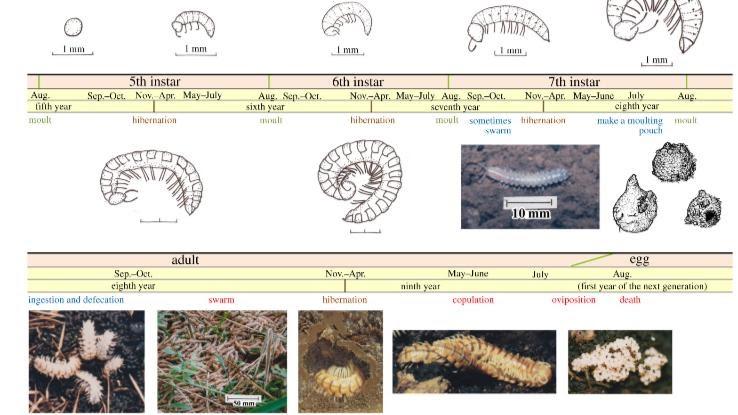

In “Eight-year periodical outbreaks of the train millipede,” the researchers found that the train millipedes are only the second-known type of creature to have a longer periodical life cycle akin to cicadas. (Other species aside from cicadas were known to have two-year cycles, but none had cycles as long as the millipedes or cicadas.) To uncover this information, the researchers studied millipedes at two sites: the Mount Yatsu site near the Koumi train line, and the Yanagisawa site in Chichibu-Tama-Kai National Park, which lies east of the Mount Yatsu site.

Researchers conducted observations at Mount Yatsu for 16 total years and at the Yanagisawa site for 21 total years, not all of which were consecutive. The sites were patrolled at least once or twice monthly. Information was also gathered from school teachers and others interested in forest fauna through the distribution of a handbill requesting additional records or information. The millipedes were surveyed with hand-sorting techniques, and 25- and 50-centimeter squares of soil were excavated to a depth of 15 to 20 centimeters to observe the bugs and effectively trace their life cycles.

The results? According to the study, “this millipede needs 7 years from egg to adult and one more year for maturation. Thus, the 8-year periodicity of P. l. a. [the millipedes] was confirmed by tracing the complete life history from eggs to adults in two different locations.” The researchers had finally gleaned a clear picture of the life cycle of Parafontaria laminata armigera. Adult females lay eggs in litter and soil in June and July, and these eggs hatch in July and August. Juveniles moult in summer and reach the adult stage in their seventh year, remaining in the same soil until they’re grown. Adults that are emerging from the soil swarm in autumn and begin to mate.

Researchers tracked seven broods — something akin to generations — of train millipedes. Overlapping cycles of those broods accounted for the most extreme mass eruptions of train millipedes, and the researchers were able to correlate the changes brood by brood and outbreak by outbreak.

Train millipedes cycled through eight-year-long generations for a century before the true nature of their life cycle was understood — even before they were called train millipedes. Until the confirmation of the research described here, periodical cicadas were the only creatures known to have a similar cycle. While this is certainly a breakthrough in the field of arthropod science, we have to wonder: What mysterious fauna phenomenon today might finally be explained a century from now?