Meet the World’s Largest Plant: A 100 Mile-Long Seagrass From Australia

Acclaimed biologist and writer Rachel Carson famously said: “In nature, nothing exists alone.” Although the line was originally posed as a critique for the actions of people, it has since become an important reminder that everything in nature is connected. When researchers from the University of Western Australia (UWA) and Flinders University set out to measure a vast field of seagrass meadows in Australia’s Shark Bay World Heritage Area, they unexpectedly uncovered another extraordinary example of nature’s interconnectivity — in what is now believed to be the world’s largest plant.

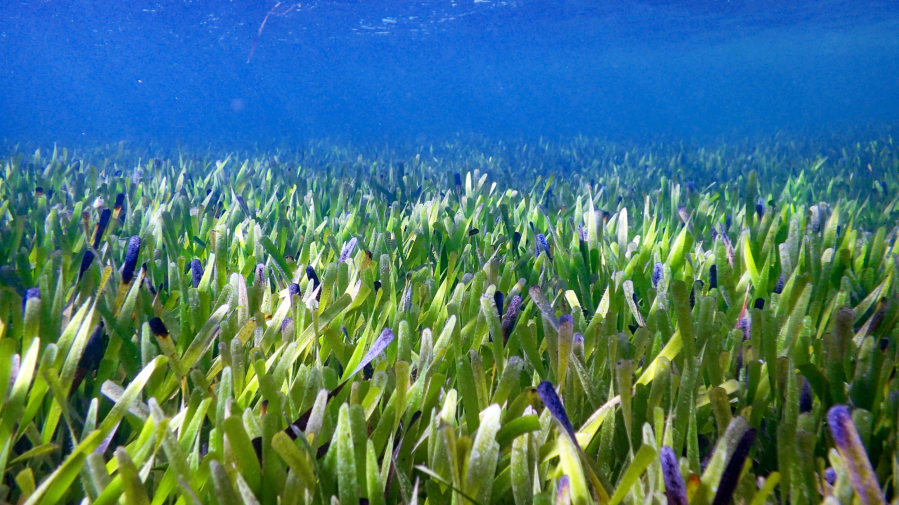

The team sampled seagrass shoots from across 10 separate locations across the bay, generating a “fingerprint” using 18,000 genetic markers. The idea was to pinpoint which plants should be collected for ecological restoration. To their surprise, the entire meadow was made up of clones of a single seagrass plant, a species known as Poseidon’s ribbon weed (Posidonia australis).

The plant stretches across nearly 112 miles and encompasses an area roughly the size of Brooklyn. Even more impressive the team estimates the plant to be at least 4,500 years old. They published their findings on June 1, 2022 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“The answer blew us away – there was just one!” said Jane Edgeloe, UWA student researcher and lead author of the study, in a press release. “That’s it, just one plant has expanded over 180km in Shark Bay, making it the largest known plant on earth. The existing 200km2 of ribbon weed meadows appear to have expanded from a single, colonising seedling.”

What Makes This Seagrass Unique?

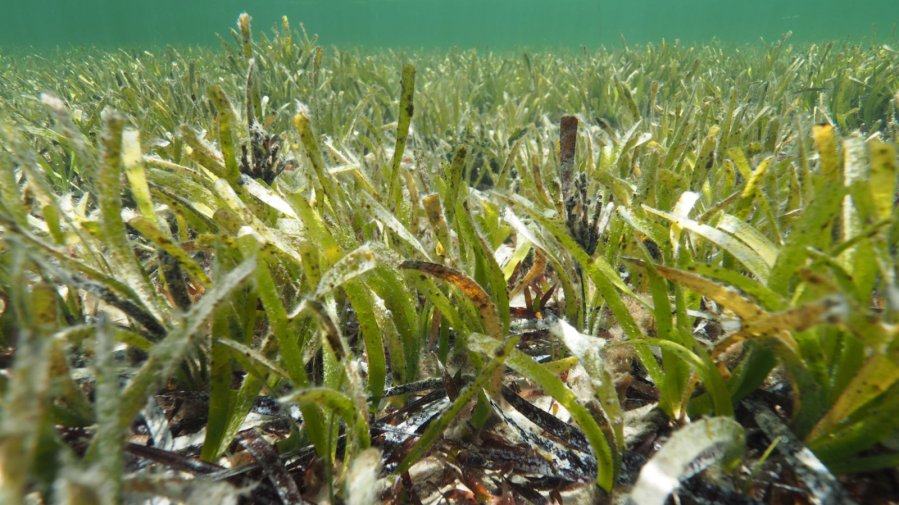

Just like land-based plants, marine seagrasses have the ability to reproduce sexually or asexually. They produce seedlings and pollen, which can carry through the water’s natural current to fertilize female flowers. In other cases, a single plant will also extend its rhizomes (stems that grow horizontally below the sediment surface), pushing out roots and shoots from underground. While the former promotes genetic diversity, the latter has the benefit of spreading quickly over a large surface area.

Shark Bay, which has gone through rapid environmental changes over the past 20,000 years, boasts unique environmental conditions protected from oceanic swells and containing large, shallow areas of sandy sediment — perfect for clonal growth and seagrass meadows. Besides its extensive size, the plant was also unique in that it was a polyploid, meaning it had received all of its chromosomes from both parent plants instead of just half from each.

“Whole genome duplication through polyploidy – doubling the number of chromosomes – occurs when diploid ‘parent’ plants hybridise. The new seedling contains 100 per cent of the genome from each parent, rather than sharing the usual 50%,” said Dr. Elizabeth Sinclair, Evolutionary biologist from UWA’s School of Biological Sciences and a senior author of the study. “Polyploid plants often reside in places with extreme environmental conditions, are often sterile, but can continue to grow if left undisturbed, and this giant seagrass has done just that.”

In the study, researchers hypothesized that the plant had an advantage over diploid organisms (those with two copies of each chromosome) due to the stressful conditions in Shark Bay. The water experiences an annual temperature shift from 62°F in winter to 86°F in summer and broad variations in salinity over its geographic range — all under very high light intensities.

Why Is Seagrass Important?

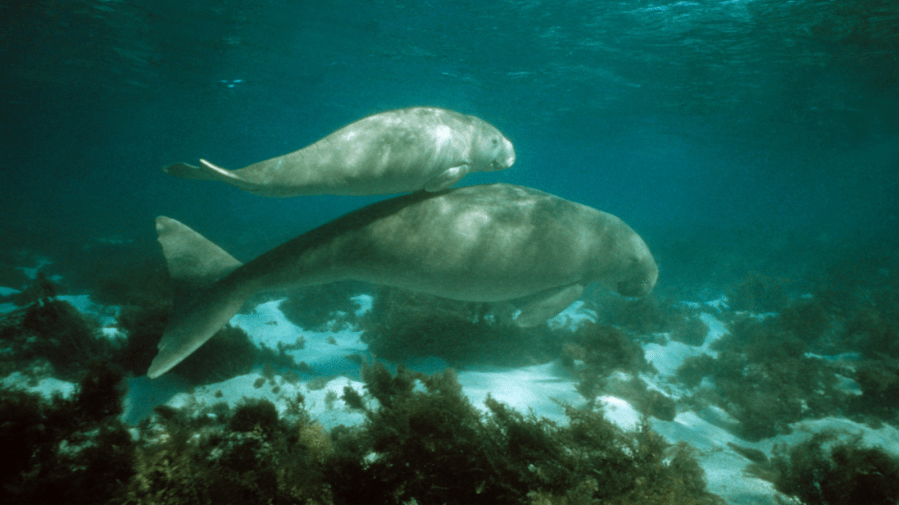

Seagrasses are vital to shallow coastal ecosystems like the ones in Shark Bay. They support an extensive variety of marine life, providing food sources and habitats for animals like fish, crabs, turtles, dolphins and octopuses. According to the National Wildlife Federation, seagrasses make the perfect nurseries for fish and invertebrates since they lessen the effects of strong currents and provide a concealed place for eggs and larvae to attach. Herbivorous wildlife such as turtles and manatees rely on the leaves and stems for food, while other organisms feed off the plankton, algae and bacteria that grow directly on the grasses themselves. Once the seagrass has died, decomposers like worms, sea cucumbers and crabs eat them as well.

Seagrasses also release oxygen into the water through photosynthesis and help improve water quality as they trap or stabilize sediments and absorb nutrients. Because of this, they’re particularly sensitive to marine pollution.

“Even without successful flowering and seed production, it appears to be really resilient, experiencing a wide range of temperatures and salinities plus extreme high light conditions, which together would typically be highly stressful for most plants” Dr. Sinclair said. The researchers at UWA have already set up a series of experiments in Shark Bay to understand how the plant has thrived under such difficult conditions.

Considering its lack of genetic diversity — which plants that deal with harsh environmental changes typically need to survive — this Poseidon’s ribbon weed represents an exciting new example of successful evolutionary strategy using polyploidy. The proposed resilience of the newly-discovered plant suggests that polyploid plants could make a favorable alternative for restoring other degraded underwater meadows in Shark Bay and similar sites elsewhere.

Shark Bay is situated at the westernmost tip of Australia and is known for possessing some of the largest and richest seagrass meadows on Earth, an ample dugong population (a relative of the manatee), and ancient stromatolite colonies. The 2.2 million-hectare protected area is also home to at least five species of globally endangered mammals.