Why Isn’t Washington, D.C., a State Already — and Why Should It Become One?

While Washington, D.C., might be home to some of the most powerful and influential government institutions in the world, this city has also floundered within a grey area between districthood and statehood throughout its existence. Many residents feel powerless to influence the results of local and national elections thanks to the district’s non-traditional status and historically unfair voting policies, which continually raises the question of whether D.C. would ultimately benefit from being granted statehood status.

The past year has been one of significant and remarkable change and disruption in many ways, and even D.C. has gotten its fair share of attention in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic and one of the more significant presidential elections in recent history. With the House of Representatives’ late-June 2020 approval of a bill that would grant the district statehood — and a revival of this push expected with another House vote on the week of April 19 — the idea has once again gained meaningful traction.

While many residents of D.C. are more than ready for their district to become the 51st state, there are still some hurdles to clear before they achieve legal and political equity with other U.S. citizens. But all things considered, with its prominent role in and rich contributions to U.S. history, D.C.’s statehood may seem long overdue.

D.C.’s Early Days Saw Flourishing Growth

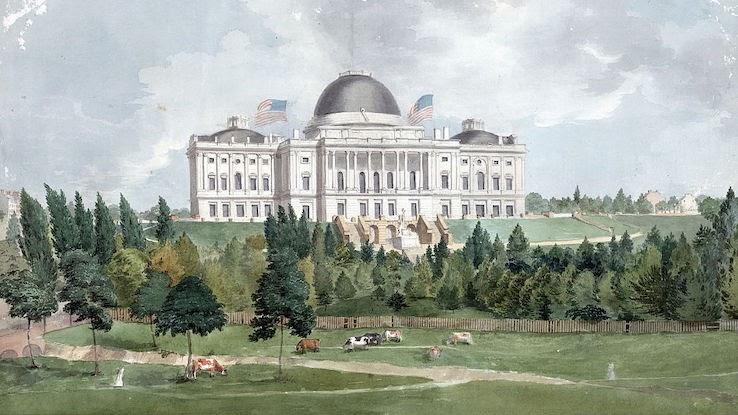

Washington, D.C., has a history that’s almost as old as the country it’s the capital of. In the summer of 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which included provisions for establishing a national capital and permanent seat of government located on the Potomac River. The then-recently ratified U.S. Constitution also provided for a special administrative federal district that would fall under Congress’ exclusive jurisdiction, which is the primary reason why D.C. was never originally part of any U.S. state.

Both Virginia and Maryland donated portions of their Alexandria and Georgetown settlements, respectively, to create the district, part of which was initially named the City of Washington — after that George, the Founding Father and first president who selected D.C.’s location. Interestingly, the Constitution specified that this district would be no larger than “ten miles square.” Thus, D.C.’s original boundary was a square, each side of which measured 10 miles long — a shape that’s mostly still the perimeter today.

In its first few years of existence, the district only housed a few thousand people, many of whom moved in temporarily to work for the politicians beginning to settle in the area. As D.C. started to take root, it underwent a few name changes, with commissioners and others eventually choosing Columbia — the female personification of the United States as a “goddess of liberty.” Congress held its first session in 1800, and in 1801, it officially enacted a law to formally place D.C. under exclusive federal and Congressional control.

From that point forward, Washington, D.C., became the official backdrop for a number of iconic milestones in the early 1800s, from landmark Supreme Court cases to the Louisiana Purchase to the War of 1812. Unsurprisingly, there wasn’t much concern about D.C.’s potential statehood during this time; the country was busy finding its footing, expanding its boundaries, funding expeditions, inaugurating new presidents and even rebuilding D.C. after British forces burned down government buildings during an 1814 raid. Residents did begin discussions about suffrage, having lost their right to vote once D.C.’s land was no longer part of any state. Life in the district was far from quiet, though, and it was about to become even more interesting.

Reconstruction Restrictions Bring Statehood to the Forefront

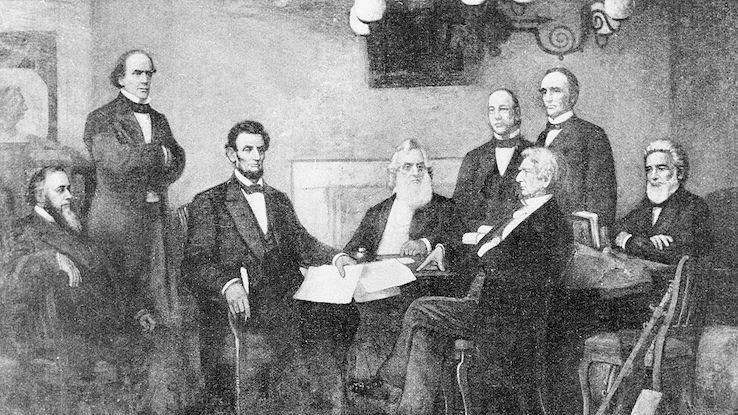

After four long years of bloodshed and tumult, the American Civil War ended in 1865 with the Union claiming victory. This marked the beginning of the reunification process of the states and the official end of slavery, but formerly enslaved people didn’t have the same rights and opportunities as other citizens or immigrants; they faced continued prejudice and violence at the hands of their white countrymen.

D.C.’s population of people who were formerly enslaved boomed after the end of the Civil War, and, for a few years, things went well for the growing African-American communities in the district. Though women were still restricted from voting in federal and local elections, Black men fought for and won the right to vote in D.C.’s municipal elections in 1867. For a brief time, these residents had democratically elected representatives within the local government.

But racism and control endured. In the 1870s, Congress abolished D.C.’s local governmental privileges and processes, including its ability to elect a mayor. This allowed the president alone to appoint the district’s governor and council, which replaced D.C.’s territorial government in 1874. Instead of allowing the predominantly African-American population to vote for presidents, Senators and Representatives, new legislation gave the acting Commander in Chief full reign over selecting D.C.’s officials.

When a push for statehood began during this period, Senators and other lawmakers used racist justifications to instead strip D.C. of its governance rights, fearing how a majority-Black voting body might affect their privilege. They continued pushing this grounds for denial of voting rights for Black people, especially when a proposal for D.C. potentially being granted Congressional representation was introduced in 1888. It took over 30 years for Congress to begin holding hearings on the matter and only resulted in a bill that would’ve allowed Congress to treat the district’s residents as citizens of a U.S. state — had it even passed.

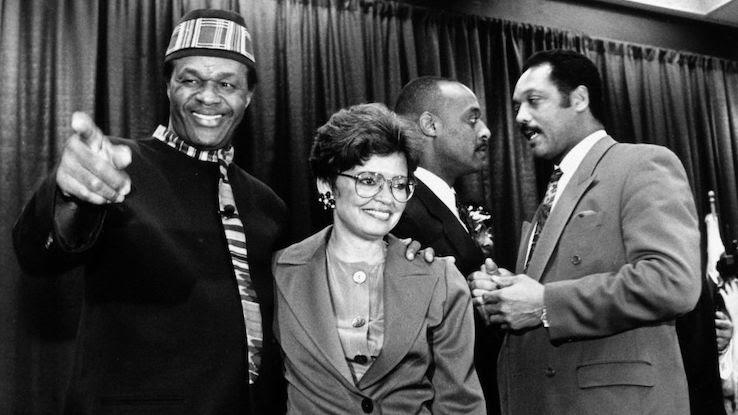

Representation Is Redefined in D.C.

In 1961, residents of D.C. secured the right to participate in presidential elections following the Twenty-third Amendment to the Constitution. However, this change came with a caveat that limited the community’s potential power. Today, as it was in 1961, D.C. is only allowed three electors to vote on behalf of residents during presidential elections — which, for a bustling metropolis of over 710,000, doesn’t seem like that many, especially considering that Wyoming (population: 580,000) also has three.

Consequently, the community’s voice wasn’t as loud as many residents felt it rightfully should’ve been; in the political epicenter of the nation, people who lived in D.C. felt they were underrepresented politically. But soon after they gained the ability to vote for president, D.C. residents obtained another government victory that buoyed them — for a while. By 1971, the district had been granted a single Representative to the House, and, in 1974, elections for Mayor of the District of Columbia again became one of the most effective ways for citizens to exert influence on local politics.

Still, there was ample open discourse on the topic of D.C’s ability to self-govern, along with its demographics. This discourse endures today, and it has some politicians worried. Voters in Washington, D.C., almost universally elect democrats — in the 15 presidential elections D.C. residents have participated in, they’ve voted for the democratic candidate 15 times. This has caused more than a little hesitation on behalf of some republican lawmakers and politicians, as those in power worry that a semi-autonomous D.C. might never elect a republican or conservative-leaning official ever again.

In addition to this, a common argument against D.C.’s statehood is that New Columbia, a proposed name for the potential state, would have the power to exert excessive influence on the federal government because of its concentration of political institutions. The U.S. government would end up relying on one state for the majority of its operations — a state that would begin voting for the best interests of its people instead of the institutions within it.

Many Supporters Argue It’s Past Time for Change

Proponents of D.C. statehood have plenty of counterarguments up their sleeves, chiefly that the district’s residents contribute massively to the success of the U.S. government but have nobody in that government — at least not in Congress — fully representing them. They’re responsible for funding the federal government with taxes and following the laws it enacts, but they don’t “enjoy the benefits and protection of having voting representation” and “this situation is simply not fair,” explains Senator Thomas Carper of Delaware. In addition, this disenfranchisement is a clear violation of civil rights in a democratic society, and D.C. statehood supporters believe this needs to be corrected.

Supporters also dispute the argument that historically and constitutionally D.C. was only meant to be the seat of the federal government by acknowledging that the Constitution has enshrined a number of other injustices, such as slavery and the disenfranchisement of women, that were later corrected. Similar changes could be made for D.C. instead of relying on the words of a 230-year-old document that no longer reflects the desires of the populace those words govern.

The District of Columbia is home to nearly three-quarters of a million year-round residents — which means that there are currently hundreds of thousands of people living in the United States who lack local representation simply because of where they live. These are hundreds of thousands of people who “[pay] more in federal taxes than 21 states and more per capita than any state.” The residents of D.C. have been fighting — and paying — for increased representation for more than a century, and many argue that it’s past time they get their dues.

While D.C. does have its single Representative in the House, this official is technically a delegate who doesn’t wield the same power as Representatives from other states and cannot vote on proposed legislation. Additionally, the district has what are called shadow Senators “to push for D.C. to become the 51st state” by maintaining a presence within Congress; however, these politicians cannot participate in full floor or committee votes. Statehood supporters argue there’s no reason to continue treating the residents of D.C. like second-class citizens by barring them from enjoying the same voting rights and representation as everyone else in the country.

What Does the Future Hold?

In June of 2020, a motion to grant statehood to D.C. was approved by the House of Representatives, but this bill, titled the Washington, D.C., Admission Act HR-51, died months later at the end of the 116th Congress. But times are changing: D.C. residents have continued holding out hope, and politicians have continued the push. The Admission Act was later revived in January 2021, and a companion bill, titled S.51, was also introduced that month with provisions to allow D.C. to join the Union as a state named Washington, Douglass Commonwealth. Both bills would give the new commonwealth equal political footing with the other states in the country, and these pieces of legislation immediately began picking up plenty of steam in the months following their respective resuscitation and unveiling.

In March of 2021, a Congressional hearing took place among the House Committee on Oversight and Reform to gauge support for HR-51, and a vote among all House members is likely to come on the week of April 19 after committee members mark up the bill — a process that allows for editing and rewriting in preparation for a full vote — on April 14. If the bill is approved in the House it will once again advance to the Senate, where it “faces long odds” and the legislative filibuster as a likely obstacle.

Regardless of the outcome of the upcoming vote, it’s unlikely D.C.’s residents will give up the fight for fair representation. As politicians realize the full importance of creating and enacting legislative changes that meet the demands of the public, and as D.C. locals continue to challenge the status quo, the district’s rise to statehood may be growing ever nearer — at last providing the representation people are fighting for.